|

|||

|

|

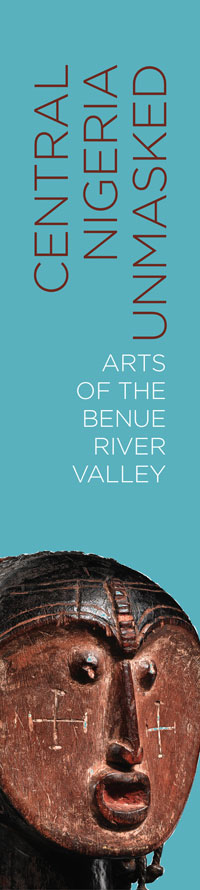

Knowledge of Benue Arts | The Lower Benue: Fluid Artistic Identities | The Middle Benue: Visual Resemblances, Connected Histories | The Upper Benue: Expressive and Ritual Capacities of Clay | Curriculum Resource for Central Nigeria Unmasked (pdf - Link to Fowler web site)  The area around the confluence of the Niger and Benue Rivers has been the home to a changing constellation of peoples over many centuries. Today it is where the Igala, Ebira, Idoma, Afo, and Tiv peoples live, among others. The lower stretches of the Benue, a mile wide during the rainy season, have long been both a pathway and barrier: a path of escape, trade, or migration, but a barrier against advancing armies and other intruders. The incursions of the Fulani dislodged peoples from the north side of the Benue, who fled to the south, often with their important ritual objects. They gradually regrouped into new communities and exchanged ideas and forms with their new neighbors. Among these were the Tiv peoples, who expanded from the south and created a cultural wedge between other peoples who had shared histories. These destabilizing events help explain the fluid identities of artistic traditions that span the Lower Benue and its open frontier with the Middle Benue. Maternal sculptures, often carved with one or more children, were used to safeguard women's health and fertility. They also protected the earth, which was thought of as female, and the well-being of crops. Their usage throughout this region speaks to their power and efficacy and makes it difficult to assign specific ethnic affiliations to works lacking documentation. Certain distinctive Lower Benue masquerades were also highly mobile, perhaps none more so than the powerful ancestral incarnations in which performers were fully enveloped in burial shrouds and prestige textiles. Specific objects offer the opportunity to tell fascinating stories of meaning, history, and interaction, exposing the forces that have shaped artistic identities over time and space.  Oba (active 1930s-circa 1950) Shrine figure (Anjenu) Idoma/Akweya peoples Early to mid-20th century Wood, string, beads, pigment Fowler Museum at UCLA; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey Kuhn X95.36.4 Photograph by Don Cole, 2010. © Fowler Museum at UCLA The Idoma artist Oba, who lived in the village of Otobi, carved this female shrine figure, called an Anjenu. Anjenu figures attracted nature spirits who dwelled in the Benue and other local rivers and were kept on shrines where offerings could be made. This sculpture by Oba lacks the finesse of the other well-known Otobi artist, Ochai (active 1910-1950), who may have been Oba's mentor. Their relationship seems to have been unusual since no formal apprenticeship system existed among Idoma carvers.  Standing female figure Jukun peoples, Wurbon Daudu (?) Late 19th-early 20th century Wood The Menil Collection, Houston L2010.62.2 Photograph Hickey-Robertson, 2010 This arresting and delicately carved female figure is related in style to sculptures documented in the Jukun town of Wurbon Daudu. They were used for individual healing and community protection. Other works from this locale are exhibited nearby and are all very distinctive, with sharply cantilevered heads, flat faces, and ornate headdresses. While sharing these features, this sculpture differs in its full-bodied female form and the rows of bangles around its lower arms, which recall Lower Benue maternal figures, some of them collected in or near Jukun towns in the Middle Benue. This piece demonstrates how Jukun arts bridge Lower and Middle Benue artistic genres, and it exemplifies the long-term historical connections among the various peoples who had followed the path of the Benue River.  Ochai (active circa 1910-1950) Crest mask (Oglinye) Idoma/Akweya peoples Early to mid-20th century Wood, pigment, plant fiber, beads Private Collection, Paris L2010.50.3 Photograph © Hughes Dubois, 2010 The work of the Idoma artist Ochai (who died around 1950) was first documented in 1958 by art historian Roy Sieber and later in the 1970s to 1980s by Sidney L. Kasfir. Unlike most other artists, Ochai was a full-time sculptor and had commissions from many villages beyond his own. He carved several genres of Idoma figures and masks, and despite their formal variations, the artist's hand is clearly evident. Ochai's carving style is bold and expressive, and his face masks seem to capture a sense of arrested movement. The whiteface masks reveal the influence of neighboring groups, especially the Igbo of southeastern Nigeria.  Figurative ax Tiv peoples Early 20th century Copper alloy, iron Fowler Museum at UCLA; Anonymous Gift X79.827 Photograph by Don Cole, 2010. © Fowler Museum at UCLA Tiv clan leaders possessed metal regalia in iron and copper alloys that indicated their status and power. Among the lost-wax cast objects associated with the Tiv are staffs, axes, snuff takers, tobacco pipes, and ritual voice disguisers. Many have figurative elements, the style of which is recognizably "Tiv." These regalia were not limited to the Tiv, however, and the axes in particular were documented among their eastern Jukun and Abakwariga neighbors, whose sophisticated metalworking may have been adopted by Tiv immigrants to the Benue River valley. |

|

Back to: NMAfA past exhibits |

|||