|

|||

|

|

Knowledge of Benue Arts | The Lower Benue: Fluid Artistic Identities | The Middle Benue: Visual Resemblances, Connected Histories | The Upper Benue: Expressive and Ritual Capacities of Clay | Curriculum Resource for Central Nigeria Unmasked (pdf - Link to Fowler web site)

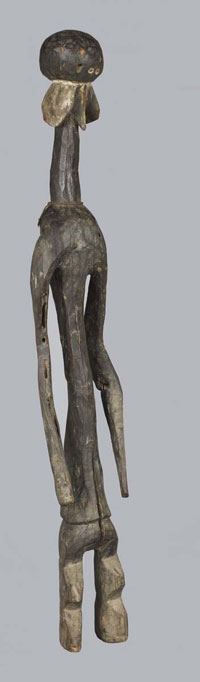

The largest and most ethnically and geographically complex of the Benue subregions is the Middle Benue. During the first half of the nineteenth century, the establishment of Muslim Fulani states and the simultaneous intensification of slave raiding dramatically impacted the diverse peoples living there. These events were followed by further disruptive outside influences in the form of British colonization and the arrival of Christian missionaries starting in the early twentieth century. Most contemporary ethnic identities within this area crystallized only during the colonial period, because the British needed them for administrative purposes, and local people embraced them out of a sense of belonging. The works of more than ten of these culture groups-with an emphasis on the Jukun, Mumuye, Chamba, Wurkun/Bikwin, Goemai, Montol, and Kantana/Kulere-are featured here. Distinctive to the arts of the Middle Benue region are sculptures in human form, hybridized human-animal horizontal masks, and remarkable vertical masks that may have functioned as "walking sculptures." The striking resemblances among these art objects speak to historical relationships and ritual alliances among neighboring peoples. All across the region, wooden figures served as intermediaries in rituals aimed at healing and protecting the community, especially from such crises as epidemics, drought, and warfare. And, horizontal and vertical masks were used in performances associated with funerals and remembering the dead, initiating youth, ensuring or celebrating a successful harvest, or healing the sick.  Horizontal cap mask Yukuben (?) peoples Early to mid-20th century Hardwood, grayish brown patina, abrus seeds, fiber Barbier-Mueller Collection, Geneva, 1015-22 L2010.42.1 Photograph © Barbier-Mueller Museum, Geneva The Kuteb and Yukuben speak languages related to the southern Jukun and live south of them around the town of Takum. Their horizontal fusion masks share the tripartite form of the others exhibited here but their greater sculptural elaboration lends them a noteworthy local flavor. Upswept bovine horns and wide snouts render them animal-like and the striations on the crests, which may refer to hair plaits, provide a human reference.  Female figure Kantana peoples (?) Early to mid-20th century Wood, resin, abrus seeds Art Institute of Chicago; Restricted Gift of Claire B. Zeisler Foundation. 1972.173 L2010.60.1 Photography © The Art Institute of Chicago Small sculptures were used by the Kantana, Kulere, and other neighboring peoples in rituals associated with healing. The figures are typically short and stocky with their heads tucked into their shoulders, and they have a red powdery surface. Without documentation, it is impossible to identify which of several peoples living south of the Jos Plateau would have made this figure.  Figure Mumuye peoples, Middle Benue 19th-20th century Wood, twine, pigment Seattle Art Museum, Gift of Katherine White and the Boeing Company L2010.70.1 Photograph Elizabeth Mann, 2010 In the Middle Benue region, figurative sculptures were used as intermediaries in ritual contexts where they could stand in for specific ancestors, the collective dead, or powerful spirits who were human-like in appearance. Mumuye figurative sculpture tends to be bold, angular, and dynamic in conception. When Mumuye sculpture first entered the art market in the late 1960s, its distinctive abstract form caused a sensation.  Bushcow mask ("small" Mangam) Kantana/Kulere peoples (?) Early to mid-20th century Wood James and Laura Ross L2010.79.2 Photography © John Bigelow Taylor  Vertical mask Wurkun/Bikwin peoples Before early 20th century Wood, palm oil, pigments Robert T. Wall Family L2010.83.2 Photograph by Don Tuttle, 2010 The vertical masks associated with the Wurkun and Bikwin peoples living north of the Benue River in the Muri Mountains are the most idiosyncratic. They were kept hidden in caves to preserve their secrecy. The only eyewitness account of a Wurkun vertical mask like this one comes from an American missionary, C. W. Guinter, who saw as many as sixteen masqueraders wearing "large wooden" masks in one memorial rite in 1925. This impressive example could have been worn with the performer's face turned sideways. It seems to have been carved intentionally to "read" differently from the front and the side views, which may have something to do with how it "walked" and was seen in performance.  Soompa (active 1920s-1940s) Chamba peoples 1920s-1940s Male-female double figure Wood Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, 2005.77; Gift of Robert and Nancy Nooter L2010.71.2 Photograph Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts The Chamba artist Soompa, who was active from the 1920s to 1940s, carved this intriguing sculpture. Anthropologist Richard Fardon and historian Christine Stelzig have identified about fifteen single and double figures in his recognizable style. This work reveals Soompa's distinctively volumetric approach to the human form. Soompa's double figures-the torsos of a male and female sharing a single hip plinth and pair of legs or alternatively emerging from a single forked pole-are among the most original sculptural inventions of the Middle Benue. Soompa's female figures have angular, flat-edged crests, while those on his males are rounded with serrated edges. The double-figure sculptures are said to be a married couple, and they were found among the apparatus of several different ritual associations. |

|

Back to: NMAfA past exhibits |

|||