Johnnetta Betsch Cole

Director Emerita

Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

I knew of Dr. David C. Driskell before we met. Like everyone else who has a passion for African American art, I was familiar with the remarkable work of the artist, scholar, curator, art collector, and professor who is known as the “Dean of African American Art.” It is an honor for me to offer these reflections on Dr. Driskell’s life and work.

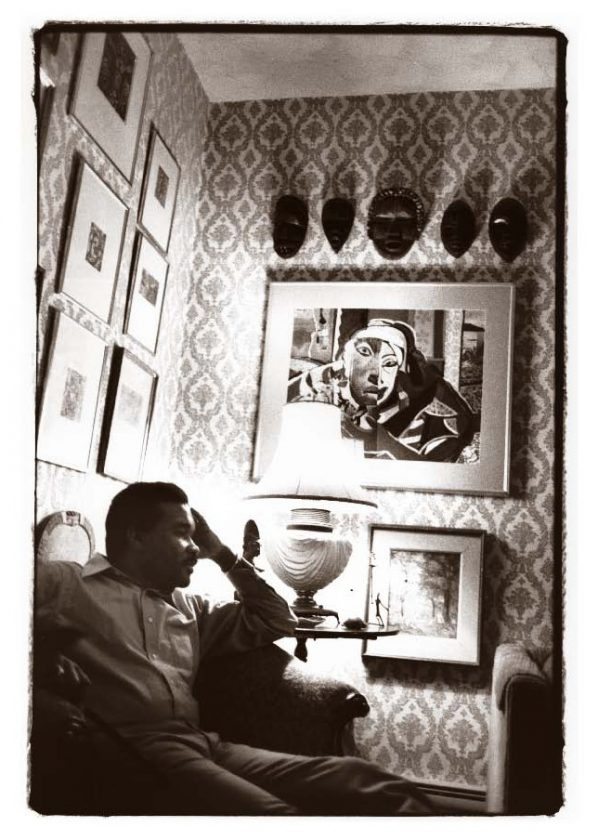

David Driskell

1980, printed 2019

Gelatin silver print

Collection of the artist

I interacted with David Driskell on a number of occasions during the 10 years that I served as the president of Spelman College. In 2009, however, when I was appointed director of the National Museum of African Art (NMAfA), we began to interact frequently in local and national art circles. Dr. Driskell’s long association with the National Museum of African Art was the impetus for our close relationship as colleagues and friends. He served on the museum’s advisory board for many years, holding the position of chair for one term, and engaged actively with the exhibitions committee.

In acknowledgement of my appointment at the National Museum of African Art, Dr. Driskell gave me Yoruba Couple, a majestic print that reigned in my office over my nine-year tenure. How might I describe this work of art, and indeed the artworks of David Driskell? In a tribute to Dr. Driskell who was a student, then on the faculty and a devoted supporter of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, co-directors Sarah Workneh and Katie Sonnenborn position his art in the ethos articulated by Léopold Sédar Senghor, poet, theoretician of Négritude, and the first president of Senegal. To describe this ethos, they draw on these words of the renowned African American writer James Baldwin: “African art is concerned with reaching beyond and beneath nature to contact, and itself become a part of la force vitale. The artistic image is not intended to represent the thing itself, but rather the reality of the force the thing contains.”

I have never seen a work by David Driskell that I did not respect and admire. However, I have a special affinity for Dancing Angel. This oil and fabric collage on canvas created in 1974 (now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum) alludes to ancient, classical, and African art, and it captures, as well, the influence of African culture on the life and mores of southern African Americans. It also offers glimpses into David Driskell’s personal history: a strip of Benin cloth recalls quilts made by his mother, and the angel refers to his father who, in his sermons as a Baptist preacher, would often talk about angels.

David Driskell’s art is included in over 26 solo and group exhibitions. Behold Thy Son, one of his most acclaimed works, is now on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture. I remember the pain, sorrow, and outrage I felt when I first saw a photograph of Behold Thy Son. This powerful work speaks to the kidnapping, brutal beating, and murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who, while visiting his relatives near Money, Mississippi, was falsely accused of flirting with a White woman. Asked why he created this work, David Driskell said he did so because he “was well aware of the power of social commentary art and its use to stir the consciousness of a people.”

Dr. Driskell designed stained glass windows for Talladega College, a historically Black institution in Alabama where he had taught, and the People’s Congregational United Church of Christ, Washington, D.C., where he was a member for many years. As part of the dedication, Ambassador Andrew Young and I were privileged to speak about the church windows—he, the east; me, the west. Dr. Driskell designed the west window around an African American female Jesus who floats above water almost level with an eye of God symbol and is accompanied by a slaving ship and a family. She carries a small cross and wears a small halo. Offering that talk, entitled “Jesus Is Your Sister,” was one of the great honors of my life.

David Driskell was a humble man who would never gloat about being a celebrated artist whose paintings, prints, drawings, collages, and mixed-medium constructions are shown in the most prestigious galleries and museums, and found in private collections worldwide. We will no longer be blessed with new works by this gifted artist, but most fortunately, there is a forthcoming retrospective of Dr. Driskell’s work opening at the High Museum in Atlanta in 2021. It will also travel to the Portland Museum of Art in Maine and the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C.

Author of numerous publications, including seven books on African American art and 40 exhibition catalogues, Dr. Driskell has consistently challenged the omission of African American art in the works of art historians and in exhibitions presented by countless curators. He was a public intellectual, who spoke brilliantly and engagingly about art as a creative practice, an act of storytelling, and a form of social history. I remember well the occasion in 2017 when Dr. Driskell and I shared a stage at Bowdoin College. At that event, the Bowdoin Museum of Art co-director Anne Collins Goodyear engaged us in a conversation about Earth Matters: Land as Material and Metaphor in the Arts of Africa, an exhibition on loan from the National Museum of African Art. Dr. Driskell had a way of sharing his knowledge—revealing the beauty and complexities of the arts of Africa and the African diaspora that could be appreciated and understood by audiences of people in- and outside of the art world. His ability to do this was no doubt honed during the years when he was a professor at three historically Black colleagues and universities—Fisk, Howard, and Talladega—and then at the University of Maryland, College Park, where he taught for 21 years.

I also had many opportunities to witness how much Professor Driskell enjoyed mentoring art students, artists, and art museum professionals, some of whom have received the Driskell Prize. Established by the High Museum of Art in 2005, the prize honors and celebrates contributors to the field of African American art. David Driskell clearly understood and supported teaching and learning about the visual arts in settings other than classrooms. He was integral to building and sustaining the David C. Driskell Center for the Study of Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora founded by the University of Maryland in 2001. At that center, it is truly impressive to behold non-university people engaged in discussions that are convened around the various exhibitions.

Photograph by Dennis and Diana Griggs, 2005

The name of David C. Driskell is etched in the annals of African, African American, and world art as a curator par excellence. Today, years since its opening, his Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750–1950 (1976, Los Angeles County Museum of Art) is remembered as the groundbreaking exhibition that set an unmovable foundation for the field.

As a curator and advisor, Dr. Driskell recommended works of art to Camille O. and William H. Cosby Jr. to consider for their private collection. Some of these extraordinary works, many of which had never been viewed outside of the Cosby homes with the exception of a work by Henry O. Tanner, were exhibited in dialogue with African artworks from the National Museum of African Art. The exhibition, entitled Conversations: African and African American Artworks in Dialogue (2014), was curated by Dr. David C. Driskell, independent art scholar Dr. Adrienne L. Childs, Dr. Christine Mullen Kreamer and Bryna M. Freyer, deputy director/chief curator and curator, respectively, at the National Museum of African Art. Each of us at the museum who worked with David Driskell on this exhibition were touched by his profound wisdom, his passion for lifting up the arts of the Black world, and his very special spirit.

I will always treasure memories of the friendship that my husband, JD Staton, and I enjoyed with David and his family. Among my fondest memories are the times spent at the Driskell homes in Maine and Maryland. Dinner always included one of David’s famous seafood dishes and one of his wife Thelma’s out-of-this-world desserts. After dinner, JD and David would retire to the piano where David played ole time gospel hymns for all of us to sing. And then, the two men-folk, drawing on the experience each had growing up in rural southern communities, would move away from the piano to line and then sing ole metered hymns.

The joy I felt in speaking on the occasion of Thelma Driskell’s 80th birthday, held at the church where she and David were members, will remain with me always. As will the image of David delighting in how their Maine home was embraced by trees that he featured in some of his artwork.

As I mourn the passing of my colleague and friend, I am beyond grateful for the honor to have known and learned from him. He lives on through his scholarship, his works of art, the students he taught and mentored, his colleagues, his friends, and his beloved family. Another way that David lives on is captured in this African proverb: “As long as a person’s name is called, that person never dies.” So let us continue to call the name of David C. Driskell.