Caravans of Gold home | Saharan Echoes | Driving Desires: Gold and Salt | The Long Reach of the Sahara |

Archaeological Imagination Station: Giving Context to Fragments / Hi Videos | Saharan Frontiers | Shifting Away from the Sahara | Teachers Guide

________________________________________

The [inhabitants of the Western Sudan] use salt for currency as gold and silver are used. They cut it into pieces and use it for their transactions.

—Ibn Battuta, 1355 C.E.

Mediterranean and Sahara—Seas of Gold Salt and gold were at the heart of a global medieval economy that bound Africa with the Mediterranean world. Artists from Egypt, Syria, Tunisia, Morocco, and Italy—to peripheries as exotic and far-flung as England—shared in a visual culture of gold.

For merchants traveling southward across the Sahara, the main attraction was West African gold, which was widely admired for its purity. In addition to its associations with material wealth, gold held powerful symbolic value. The special qualities of gold—its rarity, its sparkle and reflectiveness, its malleability, and its resistance to tarnish, as well as the difficulty of extracting it from the earth—all contributed to its value. Empires across North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe minted gold into coins and used it to make and to embellish luxury objects.

West African gold provided rulers and merchants in Saharan centers with the means to acquire goods from afar. Rock salt, mined in the heart of the Sahara, was among the most important of these. Salt, which is scarce in West Africa, is essential to human life.

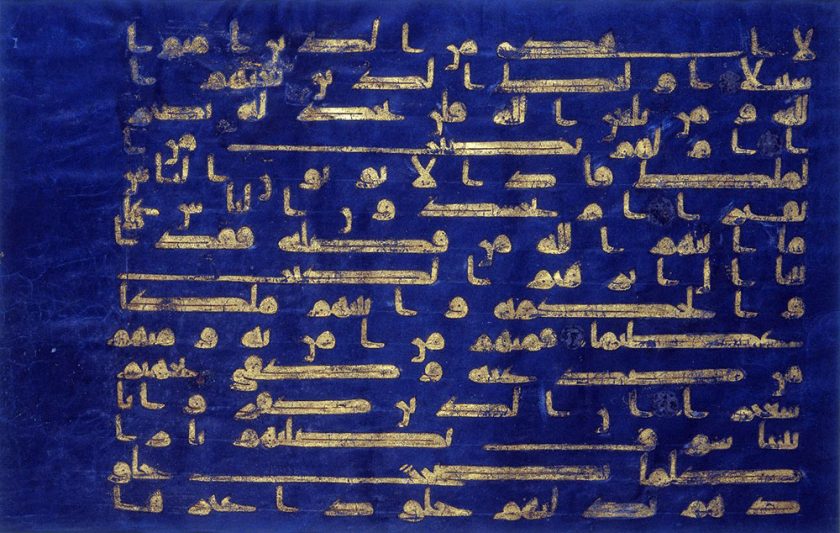

Tunisia, Iraq, or Iran

Leaf from the Blue Qur’an

9th to 10th century C.E.

Ink, color, gold, silver on indigo-colored parchment

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Francis H. Burr Memorial Fund, 1967.23

Glory of the Word | The celebrated Blue Qur’an makes extravagant use of gold and silver leaf for the script, which was laboriously applied to approximately 600 folios colored a deep, rich indigo blue. Like gold, indigo circulated widely along trans-Saharan trade networks.

The origins of the Blue Qur’an are debated. Some attribute it to Abbasid artists working in Iraq in the early 9th century C.E.; however, a possible origin in Fatimid Ifriqiya (Tunisia) has also been proposed. Fatimid control of gold coming northward across the Sahara funded the caliphate’s expansion in the mid-10th century; Ifriqiya was an important terminus for these routes.

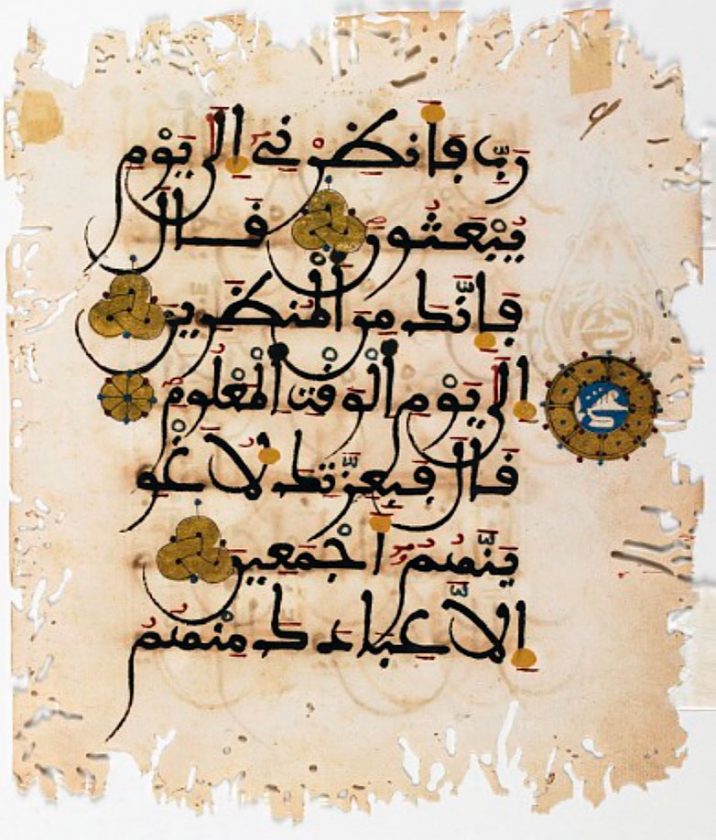

Collection of Bank al-Maghrib, Banque centrale du Royaume de Maroc

Connected with Veins of Gold | Founded by Sanhaja Imazighen from southern Mauretania, the Almoravid Dynasty (c. 1040 –1147 C.E.) emerged out of the Sahara. In its heyday the dynasty controlled parts of the Niger River, the Sahara Desert, and the Mediterranean Sea, all major conduits of trade. Almoravid mints struck dinars in many corners of the dynasty’s territory and produced more gold currency than any other empire in the western Islamic lands. Their coinage was highly valued because it was made from West African gold, which was purer than gold from any other known source.

North Africa or Spain

Folio from a Qur’an (Sura 38: 75-83)

15th to 16th century C.E.

Black ink, gold, red, blue, yellow, and green paint on parchment

Freer | Sackler, Smithsonian Institution, The Catherine and Ralph Benkaim Collection, S1997.105

Connected by Golden Words | This page from a North African Qur’an are written in black ink with gold leaf and red details. During the medieval period, a shared manuscript culture among Muslims, Christians, and Jews extended across North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Characteristics included elegant calligraphy; painted embellishments, whether figurative illustrations or geometric patterns; gold accents; and decorative leather bindings. The gold and leather used in books were imported from West Africa, and book culture likewise spread to West Africa as Islam spread across the Sahara Desert.

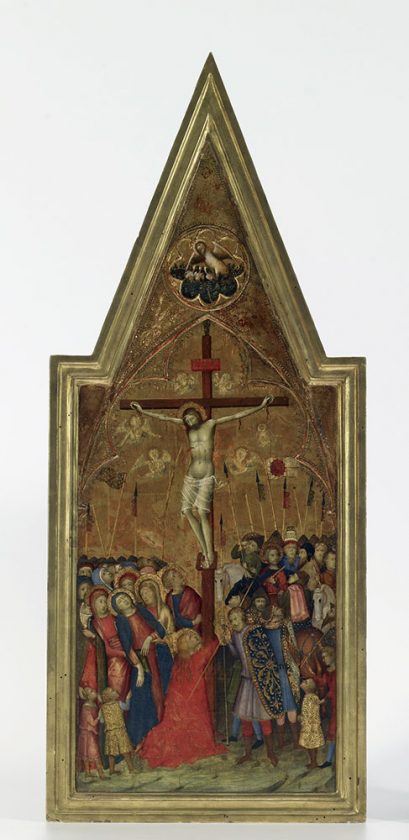

Active c. 1330–60 C.E.

Worked in Avignon, France, and Siena, Italy

Siena, Italy

The Crucifixion

c. 1350–59 C.E.

Tempera, gold on panel

The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD, bequest of Henry Walters, 1931, 37.737

Making the Most with the Minimum | Gold-ground panel paintings proliferated in later medieval Europe, where gold was associated with divinity. A small amount of gold could be used to great effect when hammered into thin sheets of gold leaf. In this fashion, painters were able to make a grand visual statement with a minimal amount of the precious material, which was imported across great distances.

Preparing a wooden panel for gilding was a laborious process. The areas to be gilded were coated with an adhesive (typically bole, a reddish clay) to which the gold leaf was applied and then burnished. Additional decoration could then be incised or stamped into the gold leaf.

Investigator Interview: The Salt Trade