Across the vast and diverse African continent specialized individuals draw upon their depth of knowledge to create works of art empowered to counter physical, social, and spiritual problems. These paintings and sculptures from the permanent collection reveal the skill and range of Africa’s artists who use diverse materials and expressive styles to craft works of art that might contain medicines, draw upon the power of the divine, or address such global issues as the HIV/AIDS crisis.

Across the vast and diverse African continent specialized individuals draw upon their depth of knowledge to create works of art empowered to counter physical, social, and spiritual problems. These paintings and sculptures from the permanent collection reveal the skill and range of Africa’s artists who use diverse materials and expressive styles to craft works of art that might contain medicines, draw upon the power of the divine, or address such global issues as the HIV/AIDS crisis.

In examining these works of art, consider how artists link the sacred and the secular, the human and the natural worlds, to explore the intersections of medicinal knowledge, power, and creative expression. How do the ideas explored in works of African art connect to your own experience?

Healing Powers

Herbalist’s staff

Late 19th to mid-20th century

Iron, stone

71 x 27.5 x 29.6 cm (27 15/16 x 10 13/16 x 11 5/8 in.)

Gift of Amb. and Mrs. Benjamin Hill Brown Jr., 76-3-4

Among the Yoruba, a large bird in the center of a gathering of birds symbolizes the capacity to control supernatural forces and the power of good subduing evil. These staffs represent the abilities of herbalists who are priests of the gods of healing, Osanyin and Erinle.

The complex imagery on this staff refers to Ogun, the god of iron and the patron of blacksmiths and anyone using metal tools or machinery. By providing the iron blades used to cut through the forest in the search for medicinal plants, Ogun facilitates the herbalist’s work. Ogun’s aggressive masculinity and spiritual powers are symbolized by the rods held in the figure’s left hand, the fan in its right hand, and the chain links at its waist. Some of the smaller birds in the form of stylized blades also refer to Ogun.

Avatars of Power

Whistle (naiba)

Late 19th to early 20th century

Wood, duiker antelope horn

17.8 x 3.15 x 2.5 cm (7 x 1 1/4 x 1 in.)

Museum purchase, 91-4-3

Kongo whistles could function as hunters’ amulets or as part of a healing specialist’s, or nganga’s, equipment. The figure on this whistle probably depicts a dog, with its body poised and ears pricked, waiting for the hunt to begin—work that takes both hunter and dog into the forest, the place where ancestral and spiritual realms are located. In healing contexts, the dog symbolizes the ability to control spiritual forces and, more particularly, skill at tracking beings intending to harm others.

Whistles were part of public performances that occurred when the nganga activated the spiritual forces contained in a power figure known as an nkisi. The whistle would have been inverted to allow its user to blow across the wide opening of the antelope horn.

Medicine Containers

Medicinal container

Mid- to late 20th century

Gourd, wood, copper alloy, plant fiber

21.1 x 9.9 x 9.9 cm (8 5/16 x 3 7/8 x 3 7/8 in.)

Museum purchase, 89-6-1

Exceptional artistry transforms functional containers for holding medicines into works of art. Among the Kwere, women healers carry medicinal oils and herbs in gourd containers. The hairstyle carved on the figurative stopper of this container is typical of that worn by girls during their coming-of-age ceremonies. The group of stoppers in this exhibition also served a similar purpose.

Stopper (detail)

Early to mid-20th century

Wood

24.5 x 2.6 x 2.4 cm (9 5/8 x 1 x 15/16 in.)

Gift of Walt Disney World Co., a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company, 2005-6-27

Functional, yet decorative, stoppers shaped as human heads and half-figures once safeguarded the contents of gourds filled with palm wine, water, or medicinal ingredients. The distinct, concave faces atop these wooden implements suggest the influence of the carving style of the neighboring Pende peoples.

Healing Imagery

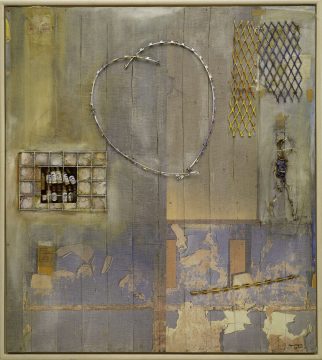

b. 1952, South Africa

Untitled

2000

Mixed media on wood

122.5 x 110 cm (48 1/4 x 43 5/16 in.)

Purchased with funds provided by the Annie Laurie Aitken Endowment, 2000-23-1

Kagiso Pat Mautloa’s abstract works are concerned with scale, size, and texture. Saturated with color, they focus on life in South Africa’s townships, creating compositions of found materials in which the harshness and simple beauties of life coexist.

In this work, Mautloa addresses the impact of HIV/AIDS upon the everyday life of township residents, bending the barbed wires that separate the haves and the have-nots in South Africa into a soothing heart shape. He created an opening in the canvas to evoke the window of an apothecary dispensing small vials of local medicine (healing and aphrodisiac mixtures). The medical gauze that coats the canvas softens the brutality associated with the barbed wire and metal grille fences. It also suggests the veil of misunderstanding and secrecy surrounding the contraction and long-term implications of living with the HIV virus.

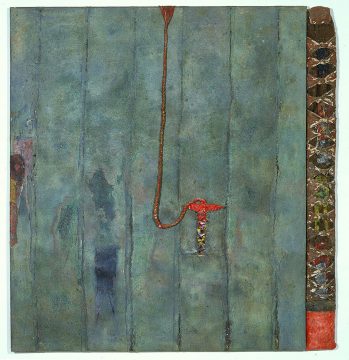

b. 1954, Senegal

Plantlike Evocation

1996

Acrylic and mixed media on canvas

140.7 x 133.5 x 7.8 cm (55 3/8 x 52 9/16 x 3 1/16 in.)

Museum purchase and gift of the Noah-Sadie K. Wachtel Foundation on behalf of Dr. and Mrs. Sidney G. Clyman, 99-11-1

In Viyé Diba’s Plantlike Evocation, the cloth strips sewn together across the width of the canvas and the addition of a packet or bundle of contrasting red material are reminiscent of west African strip-woven shirts ornamented with medicinal, protective packets wrapped in leather or red cloth.

Diba’s work is characterized by a highly sophisticated and restrained use of material and color. The artist received a Ph.D. in urban geography, and his interest in social and environmental concerns motivates his use of local and recycled materials, paying homage to them as he transforms them into things of beauty.

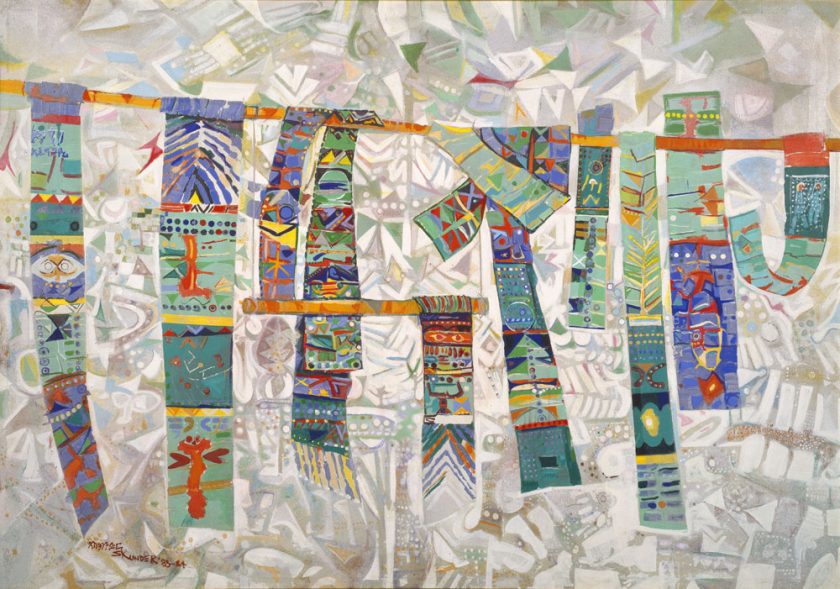

1937–2003, Ethiopia

Spring Scrolls

1983–84

Acrylic on canvas

128 x 182.2 cm (50 3/8 x 71 3/4 in.)

Museum purchase, 91-18-1