|

|

Henrique Oliveira

b. 1973, Ourinhos, Brazil

When Henrique Oliveira returned to his home in Ourinhos, Brazil, after graduating from college in 1997 with a degree in social communication, he found the resolve to change course and dedicate himself to painting. A year later, he installed his first show in a bar in São Paulo and within a few short months was enrolled in the prestigious fine arts program at the University of São Paulo. His emphasis shifted over the course of his studies from pictorial illusion to experiments with surface. He began to layer canvas on canvas like a collage, or rub sand into his paint to add texture. As he worked, he watched the wood fencing--known as tapumes--around a construction site across from his studio weather and deteriorate. A week before the end-of-year student exhibition, the fences came down. He gathered the wood and set to work on his first installation.

Oliveira's use of weathered strips of tapumes to evoke the stroke of a paintbrush or the folds of human flesh has become a trademark. His installations, combined with his ongoing explorations of the expressive movement and cumulative effects of layers of paint, have rapidly earned Oliveira international recognition. His work has been exhibited on three continents and in 2010 he was included in both the São Paulo and Monterrey Biennials and received Brazil's illustrious Marcantonio Vilaça prize for the arts. The National Museum of African Art is proud to be the first US museum to showcase the work of this emerging star as part of a dialogue with South Africa's Sandile Zulu.

|

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art

|

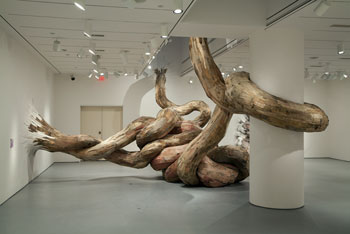

Bololô

2011

Wood, hardware, pigment

Site-specific installation, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art

Henrique Oliveira's installations to date have followed two dominant trajectories: corporeal imaginings, such as Xilonoma Chamusquius, and more painterly experiments in which the swirls and drips of thickly applied paint are reinvented in three-dimensional sculptures. Building on a series of works in which the movement of paint takes on the quality of flowing liquid, Oliveira initially considered the idea of a waterfall cascading from the gallery's skylight. As his ideas evolved, however, he took the installation in a new direction by envisioning a tangle of roots which seem to both invade and support the walls of this gallery. Like the spinal cords that inspired Sandile Zulu, Oliveira's roots let us reimagine the organic structures that support the world around us.

Each of Oliveira's installations is site-specific, conceived by the artist as a direct response to the architecture and environment in which it is situated. All are made from strips of tapumes, the fence material used to screen construction sites throughout the pulsating Brazilian metropolis São Paulo. The title of this work, Bololô, is a popular Brazilian term for a problem or confusion--for life's tangles.

|

Sketch mapping out Oliveira's ideas for this installation

|

Xilonoma Chamusquius

2010

Wood, fire, plaster, hardware, pigment

Collection of the artist

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art

Henrique Oliveira's invented title, Xilonoma Chamusquius, is part of his visual response to the artworks and processes of Sandile Zulu. Oliveira combined xilo (wood in Portuguese) with -noma (from carcinoma) to allude to a wood tumor. He arrived upon Chamusquius by adding the Latin-sounding suffix quius to the Portuguese verb chamuscar, which means "to burn slightly." His "slightly burned wood tumor" picks up on the intestinal imagery explored by Zulu in such works as Large Colon (y) Brownprint--a histopathological case, but here the inner workings and malfunctions of the body take on supernatural qualities.

Oliveira's twisted and coiled intestinal loops erupt from the wall like a malignant tumor. Early in Oliveira's experimentations with tapumes, he noticed the affinity between these weathered wood barriers and the organic barrier, skin. In his early installations, he bent sheets of pink and pocked wood into forms resembling bulging, rolling bellies. Here, outer rolls of fat have been replaced with the loops of the body's interior landscape. Oliveira worked with fire for the first time in this work, lightly singeing the edges of each strip of tapumes.

|

Untitled

2005

Acrylic on medium density fiberboard

Private collection, São Paulo, Brazil

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art

Henrique Oliveira began his career as a painter and continues to paint almost daily. As he says,

painting

is a practice that I can do every day and I believe that it gives me some kind of support to think through the installations. I have the wood, I have that type of language. At the same time, the installations give me a more clear idea of what painting is and how to solve painting problems, like how to build a painting in terms of layers.

That Oliveira builds his paintings in layers, much like a collage, is evident in the splattering of red paint atop the crackled white paint, which in turn rests atop a striated field of green. The crackled effect--created when a new layer of paint is applied to a still wet undercoat and the applications dry at different rates--and the striping, which is the result of scraping a spatula across the canvas, are techniques the artist no longer employs, thus dating the work to an earlier phase.

|

Blue Abyss

2010

Acrylic on canvas

Collection of the artist

Photograph by Franko Khoury, National Museum of African Art

Color comes alive in Henrique Oliveira's acrylic canvases. Sometimes, the artist fills a bucket with pools of vivid colors--indigo, peach, vermilion, pink and forest green--and pours it onto the canvas to see how it swirls. At other times he applies tubes of paint directly onto the canvas, stands it on edge and watches the colors flow. Once dry, Oliveira builds additional layers using these same techniques. Or, he fans out his butterfly brush to form mazelike patterns, or he sweeps a quick stroke through accumulations of contrasting colors to create petal-like applications. Each painting is constructed over the course of weeks. The result is a bold sculptural accumulation of complementary and competing patches of paint and the myriad ways it can move across an insistently two-dimensional surface.

|

Henrique Oliveira working on the painting, "Blue Abyss," in his studio in São Paulo.

Photo by Karen E. Milbourne

|

|

|

|