Section One

Central African Peoples through the Eyes of Western Photographers

During the years between the two world wars, Belgium and France consolidated the colonial infrastructure. Africans were increasingly drawn into the work force and moved to new colonial cities to find salaried employment. Photography gained importance as a means for colonial governments to record their achievements. State visits provided opportunities for the colonies to promote themselves to their home countries, and when royal family members visited the Congo, officially appointed photographers documented their trips. Some royal travelers even took photographs themselves. Elisabeth, queen of the Belgians (1876-1965), was one of the photographers whose work was widely disseminated. Her 1928 portrait of a Mangbetu woman was featured on a postage stamp.

After the Second World War, government agencies increasingly controlled and stimulated image and film making. In 1950, Belgium created the Centre d'information et de documentation du Congo Belge et du Ruanda-Urundi (C.I.D.). In 1955, Inforcongo and the Congopresse branch in Léopoldville, the capital of the Belgian Congo, assumed the functions of the C.I.D. These agencies employed many photographers, among them Africans such as Joseph Makula, a Congolese who joined Congopresse in 1957. They continued the tradition of classificatory and ethnographic documentation of the peoples under colonial rule. They also took pictures of modern towns, model cities for Africans, industry, hospitals and schools. When published, the juxtaposition of these two types of images visually established a "before and after" narrative that, in European eyes, suggested African progress towards a Western style of living.

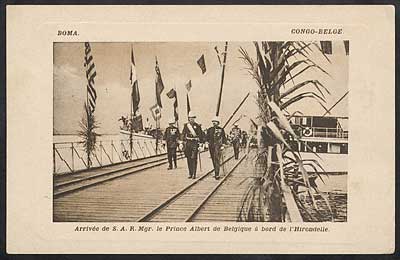

Pictured above

Prince Albert of Belgium (later Albert I, king of the Belgians) arriving in Boma on board the l'Hirondelle, Belgian Congo

Unknown photographer

1909, postcard, collotype

Published by J.P.L.W., 1909

Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives

National Museum of African Art

Smithsonian Institution

CG 36-4