At the end of the Civil War, many coastal rice plantations lay in ruins. Efforts to revive production persisted for 50 years, until a series of hurricanes between 1893 and 1916 dealt a death blow to the rice industry. Fueled by nostalgia for a lost way of life, descendants of the plantation elite memorialized the world of their parents in paintings, prints and drawings, prose, poetry and drama. What was recalled as a golden era by some, however, signaled memories of hardship and suffering for others. At the end of the Civil War, many coastal rice plantations lay in ruins. Efforts to revive production persisted for 50 years, until a series of hurricanes between 1893 and 1916 dealt a death blow to the rice industry. Fueled by nostalgia for a lost way of life, descendants of the plantation elite memorialized the world of their parents in paintings, prints and drawings, prose, poetry and drama. What was recalled as a golden era by some, however, signaled memories of hardship and suffering for others.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the figure of a stately woman balancing a basket on her head in African fashion became an icon for a group of artists and writers whose work has come to be known as the Charleston Renaissance. Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, Elizabeth O'Neill Verner, Alfred Hutty, DuBose and Dorothy Heyward and others established an art scene that can be compared to the Harlem Renaissance in New York City and to the Southern Literary Renaissance based in Nashville, Tennessee. Their salons and societies, exhibitions and publications transformed Charleston into a mecca for visiting painters, including Edward Hopper, Childe Hassam and Andrew Wyeth, and photographers such as Doris Ullman, Bayard Wootten and Walker Evans.

After the Civil War, African American farmers in the Charleston area carried vegetables and fruit to city markets in coiled bulrush baskets balanced on their head. So striking was this phenomenon that a genre of street vendor photography emerged, notably in the work of George W. Johnson. Tourists sent home postcards with images of vegetable vendors carrying produce in head-tote baskets. What was a common way of transporting goods in Africa became a symbol of African American life in the post-plantation South.

Christian missionaries journeyed south after the war to start schools for freed people. Some introduced craft production into their curricula and encouraged students to make useful objects. Basket makers created a form still popular today that imitated the bags in which Quaker missionaries carried their Bibles. In Africa in the same period, mission schools emphasized vocational training. Students learned to fabricate basketry teacups and saucers, ladies' hats, handbags and copies of American Indian baskets. Purses with handles were a novelty and for some people a sign of modernity.

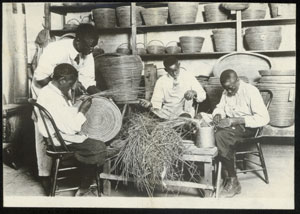

Founded by Northern missionaries during the Civil War, Penn School on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, launched a program of "industrial education" around 1900. Teaching boys to make "Native Island Basketry" was seen as a way to help farm families earn money and stay on the land. Penn School baskets found buyers across the country, particularly among the school's supporters in Philadelphia, New York and Boston. Printed promotional materials noted Penn's intention to preserve a craft with African roots. Basket making, said the Annual Report of 1910, "was brought from Africa in the early slave days." In the 1920s teachers from 46 African mission stations visited St. Helena. Calling the island "a laboratory, a demonstration of the strongest and best of the great sweeping currents of the world's life," one visitor declared her ambition to copy the Penn experiment in Angola. Penn's connection to Africa was direct. Alfred Graham, the school's first basketry instructor, learned the craft from his African-born father. Graham in turn taught his grandnephew, George Browne, who ran the basket shop from 1916 until 1950. Founded by Northern missionaries during the Civil War, Penn School on St. Helena Island, South Carolina, launched a program of "industrial education" around 1900. Teaching boys to make "Native Island Basketry" was seen as a way to help farm families earn money and stay on the land. Penn School baskets found buyers across the country, particularly among the school's supporters in Philadelphia, New York and Boston. Printed promotional materials noted Penn's intention to preserve a craft with African roots. Basket making, said the Annual Report of 1910, "was brought from Africa in the early slave days." In the 1920s teachers from 46 African mission stations visited St. Helena. Calling the island "a laboratory, a demonstration of the strongest and best of the great sweeping currents of the world's life," one visitor declared her ambition to copy the Penn experiment in Angola. Penn's connection to Africa was direct. Alfred Graham, the school's first basketry instructor, learned the craft from his African-born father. Graham in turn taught his grandnephew, George Browne, who ran the basket shop from 1916 until 1950.

During the 1960s Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and other civil rights leaders met at Penn to plan their strategy. Today, Penn Center houses a museum and conference center, and it sponsors programs to tutor public school students and to promote and preserve Sea Island history and culture.

Around 1916 Charleston merchant Clarence W. Legerton began to sell baskets at his store and through a mail-order catalog. He commissioned baskets from sewers who lived near Mt. Pleasant, across the Cooper River from Charleston. Acting as an agent for the basket makers, Sam Coakley relayed orders for baskets, and every other Saturday sewers brought their wares to his house. Under Legerton's patronage, sweetgrass basket makers earned a reliable, if modest, income. People who had never made baskets before, or who used to sew them but had stopped, were encouraged to learn from older basket makers.

Bulrush baskets, on the other hand, found a very limited market. Advertised as antiques, traditional work baskets appealed to white Southerners who were nostalgic for the old days and to souvenir seekers looking for relics of the past. Only a handful of Sea Islanders continued to make old-style baskets. With the death of Jannie Cohen of Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, in 2002, bulrush baskets went out of production. Only on Sapelo Island, Georgia, where Allen Green taught several students, have Sea Island baskets been granted a new lease on life.

Selling baskets through merchants, such as Clarence Legerton in Charleston, and directly to customers on basket stands built alongside Highway 17, families supplemented their incomes in a cash-poor economy. In the 1970s photographer Greg Day and his colleague Kate Young spent time in the basket-making community, documenting a way of life on the verge of change. Casting for shrimp with a net made exactly the way nets are still crafted in Africa, harvesting oysters and roasting them over an open fire, scraping bristles off a freshly slaughtered hog, dancing at a juke joint on a Saturday night--these rural pastimes would soon be displaced by suburban sprawl.

On September 21, 1989, Hurricane Hugo struck the Lowcountry, laying waste to coastal settlements and knocking down the basket stands that had been fixtures on the roadside since the 1930s. While the stands were easily rebuilt, the storm effectively cleared the way for new shopping malls and gated subdivisions. At the same time, the very people who were threatened with displacement were achieving recognition and status as a distinct American culture, one called Gullah or Gullah/Geechee. Once identified with the Creole language spoken by African Americans in the Lowcountry, today the term "Gullah" refers to a whole range of customs and beliefs, cuisine, domestic architecture and arts and crafts, including sweetgrass baskets.

|

|