Around 3,000 years ago, West African farmers in the floodplains of the Inland Niger Delta domesticated a hardy species of rice, Oryza glaberrima. Rice became a dietary staple of the great empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhai from the 11th to the 16th century. Along the coast, African farmers perfected methods of growing rice in marine estuaries by controlling water levels with canals, embankments, gates and hollow logs. Around 3,000 years ago, West African farmers in the floodplains of the Inland Niger Delta domesticated a hardy species of rice, Oryza glaberrima. Rice became a dietary staple of the great empires of Ghana, Mali and Songhai from the 11th to the 16th century. Along the coast, African farmers perfected methods of growing rice in marine estuaries by controlling water levels with canals, embankments, gates and hollow logs.

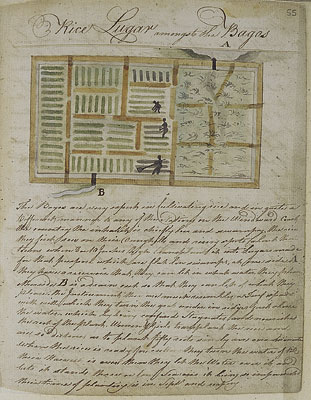

European traders not only bought rice to provision their ships but also admired African systems of rice cultivation. Geographers described how African farmers grew rice in many different environments and could obtain three crops a year by planting it along tidal rivers, in swamps and in upland fields. In 1793 slave ship captain Samuel Gamble noted that the Baga peoples in Guinea "are very expert in cultivating rice." Enslaved Africans who came from rice-growing societies planted grain left over from the oceanic voyage. In this way African rice, sometimes called "red rice," was transplanted to the American South. African rice eventually gave way to higher yielding Asian white rice (Oryza sativa). Both Asian and African varieties are grown in Africa today, where rice remains central to the diet of millions of people.

Rice features prominently in many West African ceremonies. African rituals of rice vary from place to place and are associated with a range of artworks. Weddings, rites of passage and funerals include gifts of rice. Women do much of the farm work in Africa, and celebrations that mark bountiful harvests also honor female fertility. Men perform masquerades with full-length costumes, masks and headdresses. Women's dances that commemorate their roles as mothers and cultivators feature beautifully carved bowls, spoons and baskets. Rice features prominently in many West African ceremonies. African rituals of rice vary from place to place and are associated with a range of artworks. Weddings, rites of passage and funerals include gifts of rice. Women do much of the farm work in Africa, and celebrations that mark bountiful harvests also honor female fertility. Men perform masquerades with full-length costumes, masks and headdresses. Women's dances that commemorate their roles as mothers and cultivators feature beautifully carved bowls, spoons and baskets.

Among the Dan peoples in Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire, women dance with large wooden rice spoons carved to resemble animals and people. A special spoon pays tribute to the most hospitable woman in a village. She parades with the spoon and is expected to host a feast highlighting rice. In Mali, just before the rainy season, Bamana men wearing raffia costumes and carved antelope headdresses (chi wara) dance in order to invoke the spirits to bring a successful harvest. Among the Baga peoples in Guinea and Liberia, a woman's dowry includes special ceramic bowls and baskets for storing rice, and a new bride dances with a basket on her head into which onlookers toss gifts of rice and money.

Many African peoples who worked on Lowcountry plantations came from the regions of the Congo and Angola. Rice was not grown in these areas, but people made all kinds of baskets for food processing, storage and even clothing. Coiled trays were used for winnowing maize and drying honey, large containers were made to store grain and many kinds of bowl-shaped baskets were fabricated for serving, measuring and carrying food. In North America during the heyday of rice, the pressure put on basket makers to produce large quantities of work baskets left little opportunity for variety and embellishment. Nevertheless, some Congolese and Angolan forms, notably baskets with stepped lids and footed bowls, have been reproduced continuously for centuries.

Starting in the late 1400s, Europeans sailed along the African coast, picking up cargoes of human beings, food and raw materials. Not until the end of the 19th century did they explore the interior of Africa. Coming in contact with Africa's many cultures, Europeans began to admire and collect African art, including basketry. While ancient baskets are fragile and often do not last, many museum collections contain examples from the late 1800s that are remarkably similar to baskets constructed in the American South.

|