|

|

The Arabic script was brought to northern Africa with the expansion of Islam in the 7th century. Arriving first in Egypt, it diffused throughout northern Africa before it moved into the Sahara Desert and branched off to the coasts. The earliest evidence of the script in western Africa, in the form of stone inscriptions, dates to circa 1013 A.D. An early example of the script in eastern Africa, with the point of entry being the Indian Ocean coast, is a silver seal ring from the ancient Swahili city of Shanga, dating from 780 to 850 A.D. Swahili, Wolof and other African languages are written in Arabic script.

Apart from its use in writing Arabic, which is read from right to left, and transcribing numerous African languages, the Arabic script fills an extraordinary role due to its association with the Islamic faith. Arabic is the language in which God revealed the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam, to the Prophet Muhammad. For Muslims, the script itself is a thing of sublime beauty, worthy of awe and contemplation, and it has figured significantly in the visual and healing arts of the Islamic world, including Africa.

Perhaps the most celebrated among these is the art of Arabic calligraphy, of which there are numerous historical, regional and personal styles. The works of Ali Omar Ermes (Libya), Osman Waqialla (Sudan) and Nja Mahdaoui (Tunisia) - all on view in this exhibition - testify to the creative possibilities of this aesthetic tradition.

|

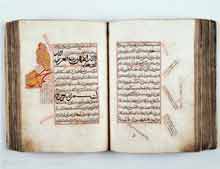

Illuminated Swahili Qur'an with 417 folios in a black leather binding with stamped designs. The text is written in an elegant, cursive script that resembles thuluth, and the formation of certain letters resembles North African maghribi script.

Siyu, Kenya.

Early 19th century. Leather and paper. 26.5 cm.

Fowler Museum at UCLA, x90.184A, B.

Photo by Don Cole.

|

Ali Omar Ermes

Qaf, "Al Alsmaie Tales"

1983

Acrylic and ink on paper

National Museum of African Art, purchased with funds provided by the Smithsonian Collections Acquisition Program,

96-22-2

Photo by Franko Khoury.

Ali Omar Ermes celebrates the rhythmic qualities of language. He refines boldly contoured Arabic letters to dramatic, abstracted forms and juxtaposes them with delicate detailed texts. This work, anchored by the sweep of the central shape, is animated by the smaller inscriptions that include lines of Arabic poetry. Interested in the relationship between literature and painting, Ermes often quotes poetry and cites its sources within his works, thereby connecting his images with larger discourses.

|

Oumarou Illa, a Malam from Niger, writing the inscription for an amulet in Boundoukou region,

Côte d'Ivoire.

Photograph by Raymond Silverman, 1987-1988.

|

|

|

|