|

In the arts of Africa, the connection between the human body and written texts has a long, complex history. From early Egyptian works to the most contemporary art forms, artists have used the body as a primary "canvas" for inscriptions--such as scarification or tattooing--or as a site for displaying graphically rich materials found on clothing or jewelry. Of all inscribed surfaces, the body may be the most politically charged template for imparting meaning. Since it moves through space, the body mediates between the public and the private spheres, allowing individuals to address ideas about gender, identity, ethnicity and class through inscribed forms of adornment.

Bodily inscription systems are reflected in Africa's traditional arts, including architecture, figurative sculptures, jewelry, pottery, decorated gourds and personal objects. They also find expression in modernist artworks, such as prints, photographs and sculptures, underscoring how both traditional and contemporary African art-though usually created for different audiences and purposes-at times employ shared aesthetic systems and a common recognition of the power of the inscribed body to convey meaning, memory and identity.

The Body Decorated

The decorated body holds cultural meaning and conveys specific information to those versed in its visual vocabulary. Body scarification and tattooing have long been viewed in Africa as marks of civilization that affirm ethnic identity, indicate rank or standing within society and signal permanent transition to adulthood. These forms of body enhancement are both rich in content and extraordinarily beautiful in appearance. In the case of scarification, touching plays a role as important as seeing. As tactile scriptures, scarification signifies the body's preparation for adulthood, marriage and the birth of children.

Just as bodies are transformed, idealized and rendered semantically rich through scarification and tattooing, many objects used in Africa are incised with graphic patterns imitating those on the skin, as seen in the pottery jar displayed nearby. These metaphoric bodies reinforce deeply held cultural beliefs about what it means to be human.

|

Barbie Loves Ken, Ken Loves Barbie

Ghada Amer, b. 1963, Egypt

1995, ed. 2.3

Fiber, pigment

Life size

Loan of the artist and Gagosian Gallery

Ghada Amer addresses text and the body through embroidery. She uses this quintessential female art form to portray complex ideas about gender stereotypes and identity. By embroidering two body suits with texts that repeatedly declare "Barbie loves Ken, Ken loves Barbie," she assigns male/female identities to two androgynous figures. In this way Amer questions gender roles, especially those based on popular American icons.

|

Pendant (tanfuk n' azraf)

Tuareg peoples

Niger

Early-mid 20th century

Silver, glass, wax

H x W x D: 8.0 x 4.4 x 0.5 cm (3 1/8 x 1 3/4 x 3/16 in.)

Museum purchase and gift of Mrs. Florence Selden in memory

of Carl L. Selden

93-6-7

The back of each of these Tuareg protective pendants, which are associated with healing and fertility, was signed in Tifinagh script. The inscriptions may be initials or a phrase: "It is I [name] who made this work."

|

Amulet ring

Undetermined peoples

Morocco

Early 20th century

Silver alloy

H x W x D: 3.2 x 3.2 x 2.4 cm (1 1/4 x 1 1/4 x 15/16 in.)

Gift of Ivo Grammet

2003-9-1

This ring is inscribed with mystical squares, two-dimensional devices whose letters and numbers cure, protect, and bring overall well-being to the wearer.

|

Storage vessel

Kurumba peoples

Burkina Faso

Mid 20th century

Ceramic

H x W x D: 64.5 x 49.5 x 50.2 cm (25 3/8 x 19 1/2 x 19 3/4 in.)

Gift of Saul Bellow

81-10-1

|

Headrest

Master of Mulongo

Luba peoples

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Mid-late 19th century

Wood, oil

H x W x D: 17.1 x 12.4 x 9.2 cm (6 3/4 x 4 7/8 x 3 5/8 in.)

Museum purchase

86-12-14

The female figure is prominent in Luba art, an indication of women's status as wives and mothers, priestesses, political advisors and spirit mediums. Elaborately carved headrests are high-prestige objects used as pillows to preserve intricate hairstyles and to foster important dreams. Their decorations reflect Luba conventions of feminine beauty that emphasize complex coiffures and scarification.

|

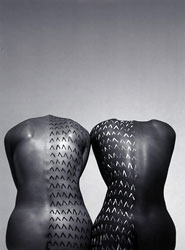

Untitled #16

Iké Udé born ca. 1966, Nigeria

1997

Iris print mounted on aluminum

H x W: 101.6 x 76.2 cm (40 x 30 in.)

Museum purchase

2003-21-2

In his Uli series, artist Iké Udé creates compelling images that combine the elegance of high fashion with the anonymity of the inscribed and disembodied self. The works acknowledge the artist's Igbo heritage by referencing the practice of uli, a woman's art form in southeastern Nigeria. While the designs remind the artist of his past-Untitled #3 brings to mind his mother's arm decorated with uli patterns-these photographs are more concerned with light and shadow, the interplay between form and script, and explorations of identity and the body.

|

|

|