|

|

Script and graphic patterns also enliven the spaces of rural and urban Africa, much as they do in the rest of the world. From commercial advertisements and graffiti to the decorative embellishments of people's homes, the spaces in which we live, work, play and worship are powerful venues for communication. Indeed, writing and graphic patterns help transform space into place.

These images are a sampling of how writing and graphic systems intersect in creative and artistic ways with spaces in Africa. Inscribed spaces are intimately connected to the human body, to notions of gender and identity, to religious beliefs and practices, to expressions of power and resistance, and to aesthetic concepts and the arts.

|

Ndebele woman painting a wall, South Africa

Photograph by Constance Stuart Larrabee, 1935-88

Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives,

Constance Stuart Larrabee Photographs, EEPA 1998-060593,

National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Ndebele mural designs communicate information about the family's identity, such as ethnic affiliation and sense of place. This is particularly significant given the Ndebele were dispersed throughout the Transvaal in the 19th century following their defeat by the Boers.

Today's complex Ndebele murals are a relatively recent phenomenon. Ndebele women began creating this genre in the 1940s with the proliferation of commercial acrylic paints and rectangular houses that provided an ideal canvas for women's artistic creativity.

|

A Moba woman uses the sharp edge of a stone to inscribe linear incisions into the wet mud plaster of a compound wall.

Nano, Togo

Photograph by Christine Mullen Kreamer, 1981

The metaphor of house as body extends to the decoration of the earthen homes common in Moba villages. The interiors of Moba compound are female spaces. Women use the long edges of faceted stones to press linear incisions into the wet mud plaster walls. Linear designs that are precise and closely spaced are especially appreciated. The Moba call these wall designs warri, the same term used for body scarification patterns that tend to be associated with feminine beauty.

|

Uli artist Agbaejije Anunobi creating a mural on an obi, a men's meetinghouse

Photograph by Sarah Adams, 2000

Uli is a historically ephemeral form of mural and body painting practiced predominantly by female artists in Igbo-speaking regions of southeastern Nigeria. Once very common in southeastern Nigeria, Uli body and mural painting were used in different contexts depending on the region. In some areas, commissioned artists painted shrines annually for local festivals. In other areas, artists painted their own homes or compound walls in honor of specific events, such as title takings or weddings.

In the 1970s, the Nsukka Group-contemporary artists associated with the University of Nigeria, Nsukka-drew inspiration from uli and nsibidi designs. Incorporating the designs into their works and experimenting with their forms and meanings, these artists created yet another context in which these graphic systems thrived. Artists in the group included Tayo Adenaike, El Anatsui, Chika Aniakor and Ada Udechukwu, Obiora Udechukwu, Olu Oguibe and Uche Okeke.

|

Uli Notes

Tayo Adenaike,

b. 1954, Nigeria.

Watercolor on paper, 1991.

|

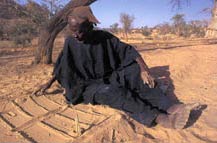

Dogon diviner Aninyu Anidzu inscribing a linear grid used in divination

Tireli, Mali

Photograph © 2001 Stephenie Hollyman

Inscription systems are also used to demarcate ritual spaces. A Dogon diviner in Mali inscribes the earth with a grid of parallel and intersecting lines to create a space where communication with the spirit world is possible.

|

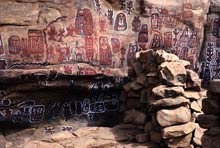

Dogon rock paintings

Songo village, Mali

Photograph by Philip L. Ravenhill, 1989

National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, Philip L. Ravenhill Collection, EEPA 1989-060.191

The Dogon peoples decorate rock shelters used for circumcision rites with motifs in red, black and white pigment. While some of the designs suggest masquerade forms and the flora and fauna of the Dogon countryside, other designs are more enigmatic and may comprise a graphic system used to transmit knowledge about Dogon culture to young initiates.

|

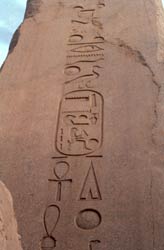

Monumental Hieroglyphs

The enormous size of the hieroglyphs on this obelisk from Karnak temple in Thebes allowed them to be read from a distance. The cartouche belongs to the pharaoh Hatshepsut (ca. 1473-58 BC) who built a pair of obelisks to the glory of Amun-re, the principle deity worshipped at Karnak.

Photograph by Diana Craig Patch, 1983

|

A Vodun priest draws a vèvè for a simbi spirit

Carrefour, Haiti

Photograph by Graham Stuart McGee, 1968

Enslaved Africans transported to the Americas during the period of the transatlantic slave trade (late 15th through mid-19th centuries) brought their writing and graphic systems with them.

A vèvè is a drawing on the ground, dedicated to a spirit. Note the Kongo-influenced dikenga sign, a cross within the circle at the center of his drawing. Engaging with time and space, it depicts the rising and the setting of the sun and symbolizes the soul's journey through life from birth to death and the crossroads.

|

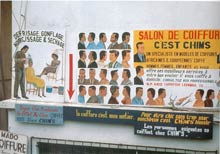

Signage above a large barber shop

Libreville, Gabon

Photograph by Philip Ravenhill, 1989; courtesy of Judith Timyan and family

African artists often use commercial advertising, ubiquitous in Africa and particularly prominent in urban areas, as a way to display their talents and earn a living. Africa's hand-painted signs-found everywhere on the continent-tap into the global marketplace of images while adopting a uniquely local idiom. Signs for restaurants and beer bars, as well as the shops of hairdressers, barbers, dressmakers, electricians and mechanics are inscribed with words in African and European languages.

|

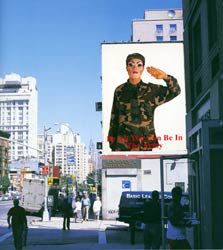

Iké Udé

Untitled (Be All You Can Be in the Army; detail), Billboard series, 1998

Mural print

61 x 162.6 cm

Photograph courtesy the artist

Artists have used urban billboards to articulate identity, history and ideology. Contemporary artist Iké Udé plays on public/private spaces in the virtual billboards he created in his Billboard series. In one work, the illusion of a "billboard" in an urban center features Udé as an androgynous-looking soldier, sporting heavy facial make-up and making a left-handed salute. It is accompanied by the headline, "Be All You Can Be in the Army." Here, image and text become a parody of sexual stereotyping in the face of the U.S. military's sexual orientation policy of "Don't ask, don't tell."

|

Graffiti wall

Dakar, Senegal

Photograph by Kinsey Katchka

1999

At the French Cultural Center in Dakar, Senegal, a block-long wall forms one side of the building where changing murals articulate various cultural, social, and political concerns. The mural here commemorates the 50th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted and proclaimed by the United Nations in 1948. These human rights include freedom of expression and access to education.

|

|

|

|