The Exhibition

Nollywood is the new face of Africa: it is modern, postmodern, bold, sexy, wicked, shrewd and with a contagious attitude worth catching.

—Iké Udé, 2016

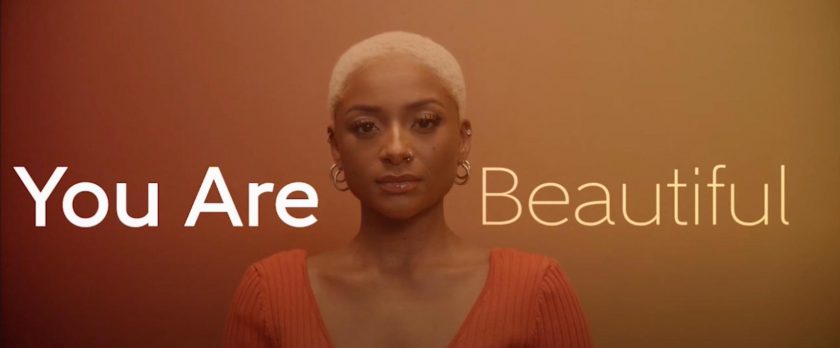

A Radical Beauty

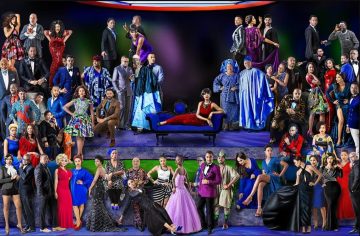

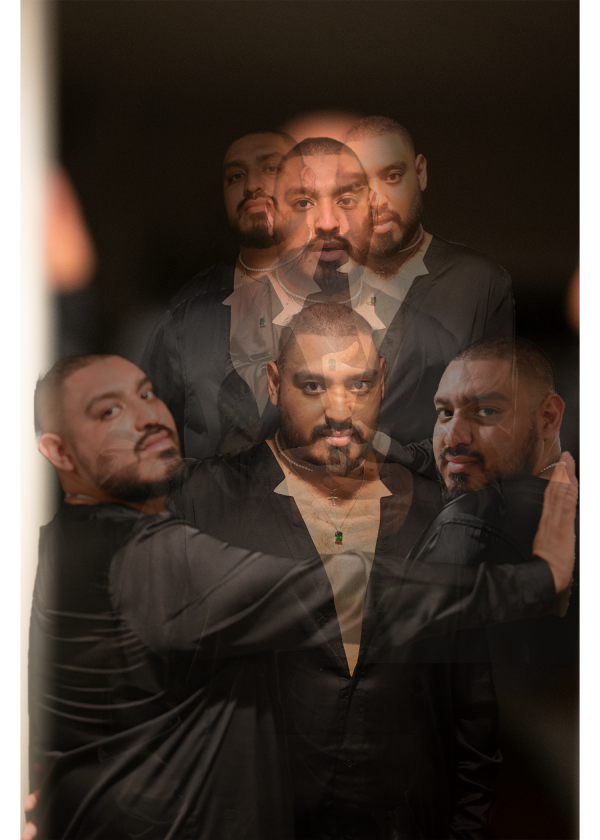

Multimedia artist Iké Udé celebrates the luminescent beauty and mystique of African visionaries by turning his lens on the talented people who drive Nollywood, Nigeria’s $3 billion film industry. Known for his performative and iconoclastic style and vibrant sense of composition, Udé’s photographs use color, attire and other markers to make elegant yet unexpected portraits. His photographs make a bold statement about the power of African identities, despite centuries of attempted erasure by Eurocentric art history and notions of beauty.

The sumptuous details in these portraits are reminiscent of what is considered “classical” portraiture, and while the subjects are glamorous and elegant, the portraits themselves represent an artistic balance of composition, form, and color. The factors that make these portraits not simply—but radically—beautiful also contribute to making the Nollywood Portraits Udé’s most ambitious body of work to date.

All artworks created by Iké Udé between 2014 and 2016. The medium is pigment on satin rag paper.

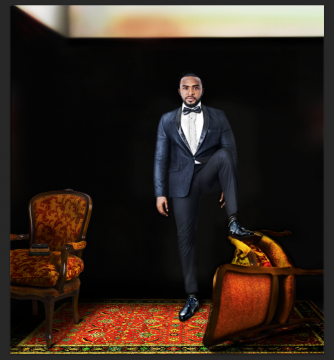

Actor, producer, entrepreneur, singer-songwriter

Born in Libreville, Gabon

Over 150 movies

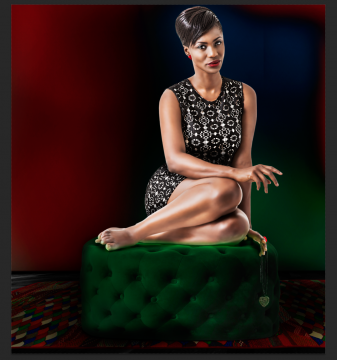

Actress, producer, director, host

Born in Lagos, Nigeria

10 movies, multiple TV series

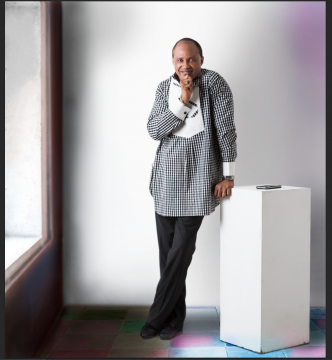

Actor, comedian, author

Born in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

Over 15 movies, multiple TV series and stage plays

Actress, director, writer, producer, model

Born in Ngor Okpala, Imo State, Nigeria

Over 100 movies

Actress, producer

Born in New York, NY

Over 30 movies, 10 TV series, 10 stage productions

Actress, director, talk show host, entrepreneur

Born in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

Over 80 movies

Actor, producer, model

Born in Lagos, Nigeria

7 movies, 5 TV series, multiple theater and musical performances

Director, producer

Born in Lagos, Nigeria

8 movies, 5 short films, 2 documentaries, 14 TV series

Director, screenwriter, producer

Born in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

Over 200 movies

The exhibition was guest curated by Selene Wendt.

Iké Udé

“Artistic truth is superior to quotidian truth.”

—Iké Udé, 2017

Throughout his career, artist Iké Udé (b. 1964, Lagos, Nigeria) has consistently challenged distinctions between art, performance, and style and has positioned himself at the forefront of each. Udé is perhaps most widely recognized for his performative, often autobiographical, approach to photography, which is typically bold, ironic, playful, and inquisitive.

With the launch of his art, culture, and fashion magazine aRude in 1995, Udé set the standard for what would become a trend of similar magazines worldwide. The title pays homage to the quintessentially stylish Jamaican rude boys of the 1950s and ’60s.

With the Nollywood Portraits, the artist captures the essence of each of his subjects with the eye of a master painter. A keen student (and critic) of art history, Udé brings in stylistic elements reminiscent of David (1784–1825, French), Ingres (1780–1867, French), Sargent (1856–1925, American), and Raphael (1483–1520, Italian)—as is evident in The School of Nollywood mural. Udé paints with color and light to create portraits that are tweaked to perfection through a keen attention to detail and use of unusually vivid, vibrant colors. As such, the Nollywood Portraits come across as both timeless and contemporary.

Udé’s photographs speak the rich visual language of classical portraiture, while offering a timely discussion about the social and cultural impact of Nollywood. These portraits convey the presence and elegance of those who have made Nigerian cinema what it is today: a globally recognized movie industry that has captured the hearts of fans worldwide.

—Iké Udé, 2016

About Nollywood

“Nollywood is Africa’s vivid mirror par excellence.”

—Iké Udé, 2016

Click on the image to watch the video

Nollywood in Focus

1:53 min

Iké Udé, filmmaker and director, Osahon Akpata, project manager

Nollywood, a term coined by New York Times journalist Norimitsu Onishi, refers to Nigeria’s prolific three-billion-dollar film industry. Created by Nigerian actors, writers, producers, and directors who wanted to tell “home-grown” stories, the industry has powerfully shaped how Nigerians and other Africans see themselves and are seen by others. Since the early 1990s, Nollywood has been a vital part of a transnational, transcontinental conversation on Black self-representation that extends from South Africa to Kenya, and as far west as Jamaica and the United States. The fact that Nollywood has its own capital in the United States (Houston) demonstrates its ever-growing global impact.

Each year, Nollywood produces more than 1,500 films in English, Yoruba, Hausa, Igbo, Itsekiri, Edo, Efik, Ijaw, Urhobo, or one of the other more than 500 languages spoken in Nigeria. Ranging from stories of mythic characters to Nigerian kings and their courts, long-suffering wives, Bible-wielding pastors, business tricksters, glamorous young professionals, and émigrés stranded in New York or London, these films reflect the drama and complexity of life—and representation—in Lagos and beyond.

Portrait gallery

Bring your beauty to the museum. Strike a Pose. Tag your art #nollywoodsmithsonian and you might see it here!

The Stars Speak

Click on the image to watch the video.

Three Schools of Photography

Emerging artists in the field of photography participated in a unique opportunity to learn from celebrated photographer Iké Udé

Three Schools of Photography Online Exhibition

Iké Udé is a Nigerian American artist, author, and publisher perhaps most widely recognized for his bold, ironic, and inquisitive approach to photography. He enthusiastically agreed to connect with, instruct, and inspire the next generation of creatives in the masterclass Three Schools of Photography held in collaboration with the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art.

An open call generated many applicants who showed a distinct level of creativity, knowledge in terms of either genre or technique, and aspiration but who could also benefit learning from Udé. Among them were emerging artist photographers Tracy Meehleib, RA Dean, Lola Lombard, Shedrick Pelt, Niat Afeworki, and Gayatri Malhotra. Udé shared with them his perspectives and techniques relating to cameraless photography. The class covered the history of camera obscura, the use of multiple frames to make a single image, and the direct exposure of objects to photosensitive surfaces. Upon completion of the masterclass, participants created cameraless photographs that incorporated lessons learned.

Tracy Meehleib

I am an American photographer based in Washington, DC. Shooting primarily in DC, I focus on street photography and street portraiture. I am a member of Women Photojournalists of Washington, and my work is in the collection of the Library of Congress.

R A Dean

The first school of photography is street photography where you capture moments. The second school is more intentional/composed using elements of photography, and the third school of photography is camera obscura (lighting a dark room) creating an image using editing processes available in the 11th century. It wasn’t until the 16th century when painters like Vermeer and Rembrandt began to use the camera obscura process where the subject would sit in front of the sunlight, the image reflected through a lens and onto a wall in the dark room.

In the spirit/essence of Alhazen, inventor of the camera obscura, I used a modern, ubiquitous tool—my phone—to capture and process these images.

Lola Lombard

I typically tell stories through multidisciplinary methods, creating as I see things in my imagination. Here, however, I took a completely different approach by experimenting with the properties of cyanotype paper, using only found elements and direct physical action to record a factual visual diary.

Rehoboth Diary captures a specific summer day at the beach. You may recognize coastal wildflowers, pine needles, and leaves akin to moving butterflies sighted earlier on a morning bike ride. A citrus garnish and the ringed condensation of a drink appear. I washed water from the pool over my art, dripping it from my hair onto the paper, and dried it in the noonday sun. In Time & Tide I took art supplies to meet the ocean itself and washed the paper with sandy ocean water. I’ve physically layered one of these images over Rehoboth Diary as a collage representing the two places I swam over the course of the day. I finalized my experiments with digital photography at sunset and then composited these earlier cameraless experiments into them. The integrated result evolved into something completely new—Rehoboth Saltwaters. It feels the most impactful and real for me. lolalombard.com/photographylolalombard.com/photography.

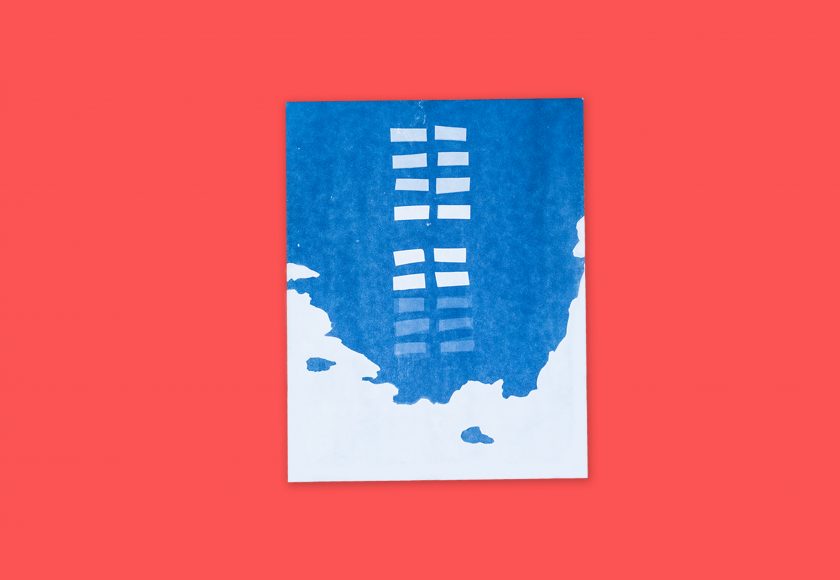

Shedrick Pelt

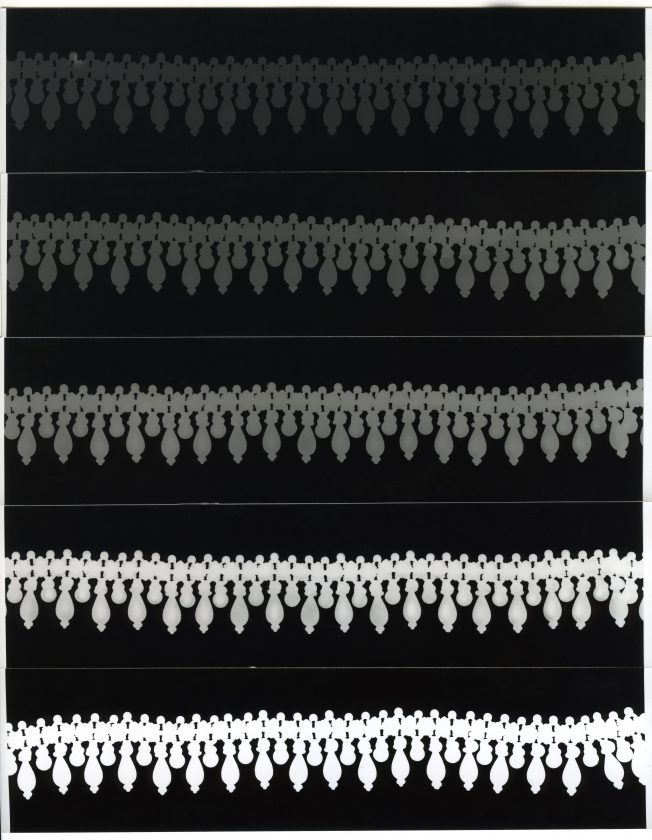

The journey as an artist continually intersects with a tribal experience. We find comfort, strength, and inspiration through those closest to our story. Adding levels of spirituality to an already divine undertaking. This series of works titled Three Tribes bears witness to the battle an artist is willing to endure in the name of his or her craft. Through the use of an alternative printing process, cyanotype, and fashioned after the war shields of some of Africa’s fiercest tribes the (Luo, Maasai, and Zulu), these cameraless photographs, activated by the light from the sun speak to a path to creativity I boldly explore.

http://www.sdotpdotmedia.com/

Niat Afeworki

My interest in photography began with my father. Growing up, he documented many moments of our life through film photography and videography, capturing moments in our daily life, relationships with loved ones, celebrations and cultural festivities. I fell in love with the medium as I sought to capture and translate the confidence and beauty I witnessed and felt from the people around me. My images mark moments of my life, capture my loved ones as I see them, and the intimacies of my interpersonal relationships. They are my histories and memories evoking sensorial nostalgia, feelings of comfort, pleasure, and love which sustain me.

Gayatri Malhotra

I am a photojournalist with a focus on gender equity, social justice, and human rights. My photographs are intended to be an advocacy tool to inspire action, spark conversation, and empower communities of color with high-quality photographs that represent them, their voices, and their lived experiences in the fight for racial justice and human rights. I am passionate about documenting the inherent strength and resilience of women and committed to using photography for social impact and change.

For the cameraless assignment, I created photograms, a type of photography that only uses photosensitive paper and light. By manipulating light, I documented some of my mother’s traditional Indian jewelry that has been passed down over the years. In the photogram A Visual Enchantment, she placed a silver choker on the photosensitive paper and exposed it to light for small increments of time, creating a gradient effect.