The Divine Comedy Poetry Contest

Announcing the winner of the Divine Comedy Poetry Contest: Fred JoinerWatch as the artist reads the winning poem.

Below as Above

after the harmattan has emptied his last

gasp and wheeze, & we have shaken loose his dust

from our bodies and found shelter

from the Sahel’s certain heat,

when the water returns and the river is high,

this bit of sun bittered earth becomes a stage, a show

for every sweet thing we have held

back in the swelter,

our hands thank the sky, a simple wave is still a worthy praise,

our feet thank the dust and the shallows

one, for the friction that helps shed the old,

the other, for the waters that soothe new skin,

our thighs thank the soil, the unseen

nourishment for the long season without,

our hips thank the moon,

for the pull on the tides;

the orbit of gratitude, music over our heads

our mothers’ mother’s song, a chant pulled

down from the heavens, or a blessing drawn

up out of the soil’s new bounty.

About the winner

Fred Joiner is a poet and curator living in Bamako, Mali. His work has appeared in Callaloo, Gargoyle, and Fledgling Rag, among other publications. Joiner is a two-time winner of the Larry Neal Award for Poetry and a 2014 Artist Fellowship Winner as awarded by the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities. Most recently, one of Joiner’s poems was selected by curator and critic A.M. Weaver as part of her 5 x 5 public art project, Ceremonies of Dark Men. As a curator of literary and visual arts programming, Joiner has worked with the American Poetry Museum, Belfast Exposed Gallery (Northern Ireland), Hillyer Artspace, Honfleur Gallery, Medina Galerie (Bamako, Mali), the Phillips Collection, the Prince Georges African American Museum and Cultural Center, and more. He is the co-founder of The Center for Poetic Thought at the Monroe Street Market in the Brookland neighborhood of Washington, D.C.

Artist Statement

Recently, my work has been engaged with my relocation to Bamako, Mali, and navigating the language, art, and culture in my new world. Overall, my work has been concerned with visual art, place, migration, and how language works for and against us.

“Below As Above” was inspired by Abdoulaye Konaté’s La Danse series.

b. 1953, Mali

Dance of Kayes from La Danse series

2008

Textile, each: approx. 246.4 x 170.2 cm

(97 x 67 in.).

Collection of Saro León

Revolving; and the rest unto their dance

With it mov’d also; and like swiftest sparks,

In sudden distance from my sight were veil’d.

—Book III, Canto VII, lines 6-8, from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (trans. by H.F. Cary, London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1892)

b. 1977, Angola

From Oikonomos, Luanda series

2011

C-prints Framed

Each: 105.4 x 105.4 cm (41 1/2 x 41 1/2 in.)

Collection of the artist, courtesy A Palazzo Gallery, Brescia, Italy

Photograph courtesy A Palazzo Gallery, Brescia, Italy

What aileth thee, that still thou look’st to earth?

Began my leader; while th’ angelic shape

A little over us his station took.

—Book II, Canto XIX, lines 51–3, from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (trans. by H.F. Cary, London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1892)

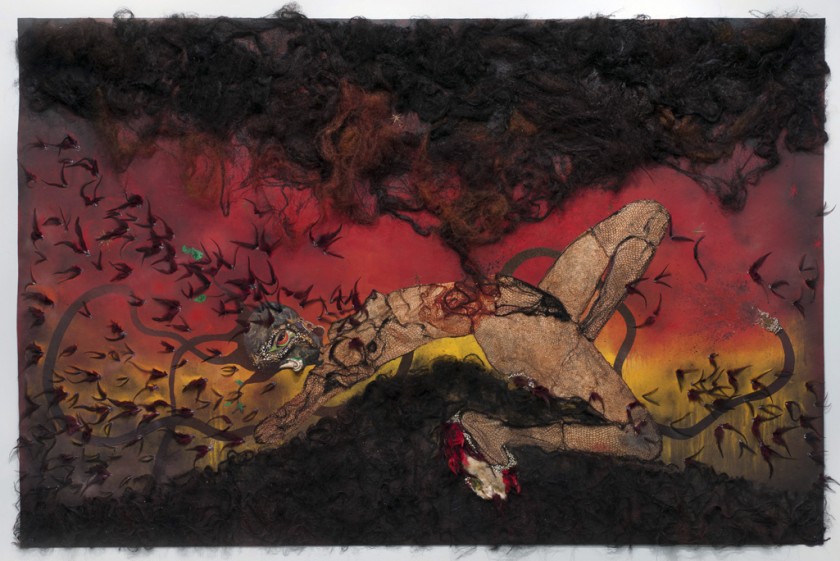

b. 1972

Kenya.

The Storm Has Finally Made It Out of Me Alhamdulillah

2012.

Collage on linoleum

193 x 295.9 x 10.2 cm

(76 x 116 1/2 x 4 in.).

Collection of the artist, courtesy Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects

My sage guide leads me, from that air serene,

Into a climate ever vex’d with storms:

And to a part I come where no light shines.

—Book I, Canto IV, lines 146–8, from The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (trans. by H.F. Cary, London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell & Company, Ltd., 1892)

About the contest

The exhibition The Divine Comedy: Heaven, Purgatory, and Hell Revisited by Contemporary African Artists, curated by internationally acclaimed writer and art critic Simon Njami, reveals the ongoing global relevance of Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century epic as part of a shared intellectual heritage. Among the artworks in the exhibition are original commissions and renowned works by more than 40 of the most dynamic contemporary artists from 18 African nations and the diaspora, including celebrated artists Nicholas Hlobo, Julie Mehretu, Wangechi Mutu, and Yinka Shonibare MBE. The artists explore the themes of heaven, purgatory, and hell and probe diverse issues of politics, heritage, history, identity, faith, and the continued power of art to express the unspoken and intangible.

Individuals were invited to submit an original work of poetry inspired by a work in The Divine Comedy exhibition. Over 40 submissions were submitted from all over the world, including Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Italy, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Uganda, South Africa, Tanzania, the United Kingdom, and from many states across the United States. Entering poets ranged in age from 19 to 72.

Submissions were judged anonymously by a panel of poetry experts, in consultation with National Museum of African Art staff

- Carolyn Forche, Director, Georgetown University Lannan Center for Poetry and Social Justice

- David Pike, Professor, American University, Department of Literature

- Charif Shanahan, Programs Director, Poetry Society of America

- Diane Boller, Editor, Poetry Daily

- Don Share, Editor, Poetry Foundation/Poetry Magazine

Submission to The Divine Comedy poetry contest does not preclude an individual from submitting his or her work to other venues for publication. Copyright to the work remains with the author.

“Ode” by Pélagie Gbaguidi

The exhibition The Divine Comedy features works inspired by the text and themes of Dante Alighieri’s 14th-century epic poem of the same name. Poetry inspires art—but art also inspires poetry. Artist Pélagie Gbaguidi wrote her own poem, “Ode,” to accompany her 42-foot painting, Dansleventreduserpentdanhomê, featured in the heaven section of the exhibition.

Open to read “Ode” by Pélagie GbaguidiNo objects, no subjects, no concept

Only the breath

Pieces of wood, pieces of oneself

Free choice

Delicate work

Not consumable

Work marked by an inhumanity to be shut up and undone

Work humble as a self-donation

An urgency to unveil taboos

A meditating work

As close to the physical

As an x-ray of the world, the instant

of a collective globality

As the transplant of something foreign into self

Sign of birth

Sign of becoming

What sign in the dawn of a new era?

We are eternal.

Neither dead nor alive

Who are they?

No answer

We are at an impass

The lie has lasted too long

Spirits awake

They convoke us

They undress the discourses

Five hundred years later, nobody claims them?

For all that, do the spirits give up?

At night, they sketch a sepulcher: truth

They are afraid of being forgotten

Not of death, nor of love, nor of hate

They are afraid of being forgotten

But you have so much to do; other forgotten ones are

dying in the waves of Lampedusa

What part of the lie is still hiding

What debate to invoke again; they yell:

“restitution” in unison,

But where to go?

What other banks

Chained to restore historical truth

They will not be able to die any more

Not shame not vanity not culpability

Must accept that the negro left

a long time ago, that his evocation is but the residue

of a past thought

Five hundred years later, nobody claims them?

For all that, do the spirits give up?

They are the witnesses

They are the bread and the yeast of your descendance

“Take care of yourselves,” they say

So that in five hundred years your descendants will

Acknowledge you.

No objects, no subjects, no concept

Only the breath

Pieces of wood, pieces of oneself

Free choice

They don’t ask to be loved, but to be placed on a pedestal

In your memory

When the last human disappears,

his shadow will be his witness

They will be there, brave pieces of wood to save

the imagination of the world.

Translated by Mira Joos and Anne Gregory

©pelagiegbaguidi8april2015

All images:

Pélagie Gbaguidi

b. 1965, Senegal

Dansleventreduserpentdanhomê (detail)

2013

Acrylic on canvas, marouflage

208.3 x 1308.1 x 6.35 cm (82 x 515 x 2 1/2 in.)

Collection of the artist

Photograph courtesy the artist

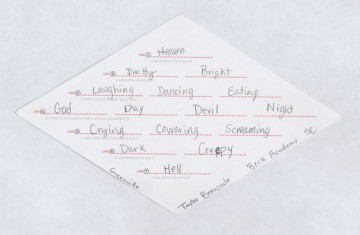

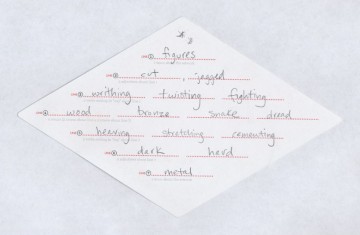

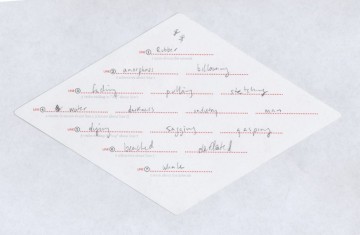

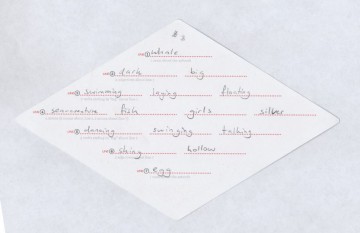

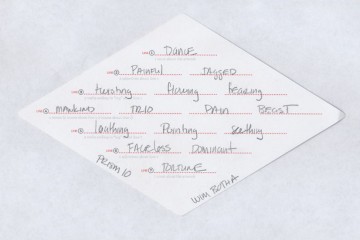

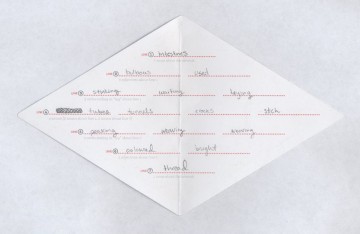

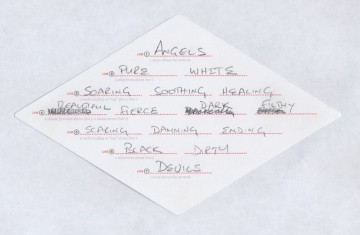

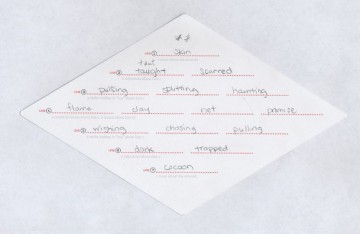

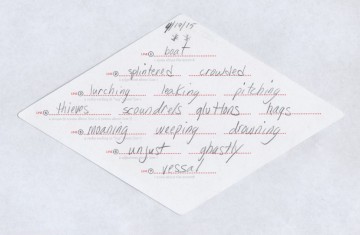

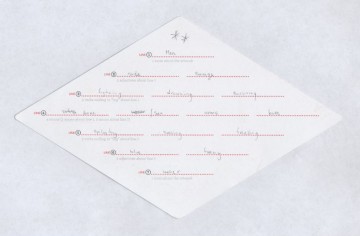

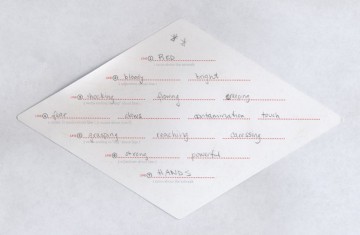

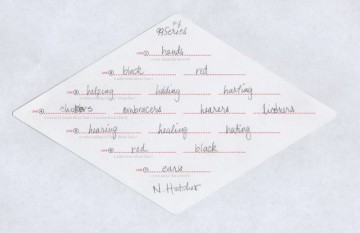

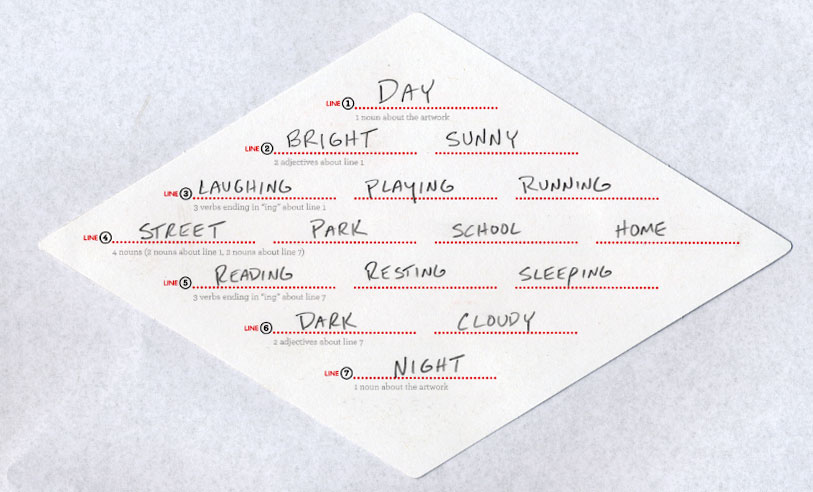

Diamante poem

An unrhymed, seven-line poem is called a diamante (dee-uh-MAHN-tay), Italian for diamond. The beginning and ending lines contain subjects—which can be synonyms or antonyms—and are the shortest, while the lines in the middle are longer, giving diamante poems a diamond shape.

Open for more information on how to compose a diamante poem

Create a diamante poem about an artwork

1. Choose two nouns about the artwork: one noun for line 1, one noun for line 7

2. Choose two adjectives about line 1

3. Choose three verbs ending in “ing” for line 1

4. Choose four nouns: two about line 1, two about line 7

5. Choose three verbs ending in “ing” for line 7

6. Choose two adjectives about line 7