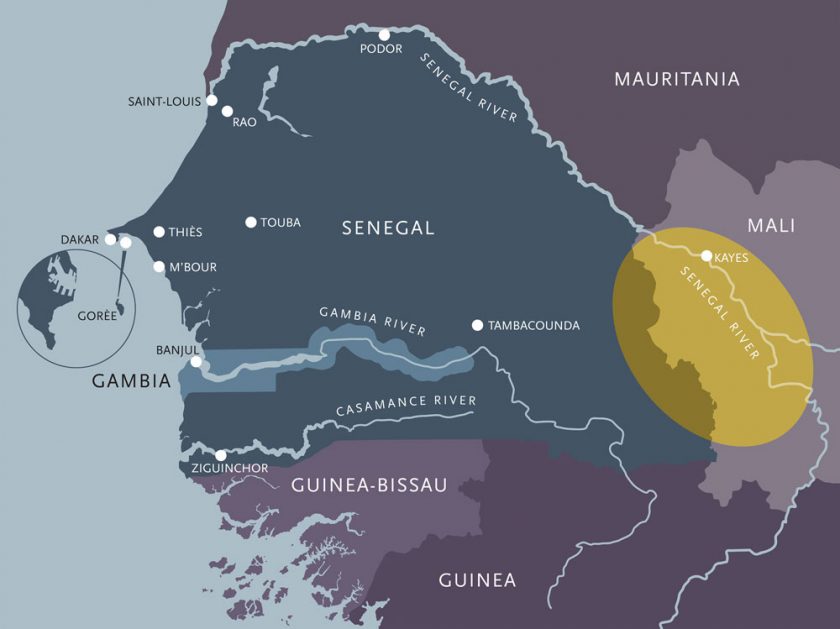

Senegal’s unique and long-standing history of gold- and metalsmithing is evident in the archaeological excavations of the Rao region. Located near Saint-Louis, in northwest Senegal, this site yielded one of the most technically sophisticated golden regalia of Africa—the Rao pectoral.

No other commodity drove medieval trade the way gold did. Historical accounts cite Bambouk, which was mined from as early as the 4th to at least the 19th century, as one of the earliest and most important gold-mining territories in West Africa. It was Bambouk and then Galam, both along Senegal’s “River of Gold,” that first drew Europeans to the region.

From the 15th century onwards Europeans traded along the coast of West Africa. Yet, they touched only the perimeter of the vast, centuries-old trade network that stretched from the Middle East, to North Africa and throughout much of the African continent. Goldsmithing techniques, styles, materials, and ideas—which particularly influenced jewelry—were readily shared because gold, which was made into twisted earrings or rods, was easily transported. For hundreds, if not thousands of years then, Senegalese gold jewelry has penetrated a sprawling network of style and material that overlaps and defies geographical confinement.

1325–1387, b. Palma, Majorca, Spain

Worked in Palma, Majorca, Spain

Catalan Atlas detail depicting Mansa Musa with gold

1375

Paper and ink

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Gold fever. In the Catalan Atlas, one of the most important maps of the medieval world, Malian ruler Mansa Musa is shown holding a large nugget of gold. Famed for his vast riches—particularly his enormous caches of gold—his renown spread like wildfire after his lavishly appointed and flamboyant pilgrimage to Mecca, which ignited North African and European desires to seek out this fabulously wealthy Malian empire and its gold.

Fusing a Senegalese Style

Senegalese blacksmiths have been working with metals since the first millennium B.C.E. and likely adopted certain gold- and silversmithing techniques after coming into contact with early North African traders by at least the 11th century. North African Imazighen, Jewish, and Islamic styles influenced Senegalese techniques and patterns long before the discovery of other West African gold mines and the arrival of Portuguese explorers in the 15th century, fusing into a West African aesthetic that later included importations from the Middle East, Europe, and India.

Yet, styles that are distinctively Senegalese also emerged, as evidenced in the ancient Rao pectoral, a famous 12th-century archaeological find that features many of the techniques still being practiced in Senegal today. Over the centuries, contact between cultures has brought about artistic and aesthetic changes as Senegalese goldsmiths experimented with new materials and technologies while modifying existing motifs.

Dakar, Senegal

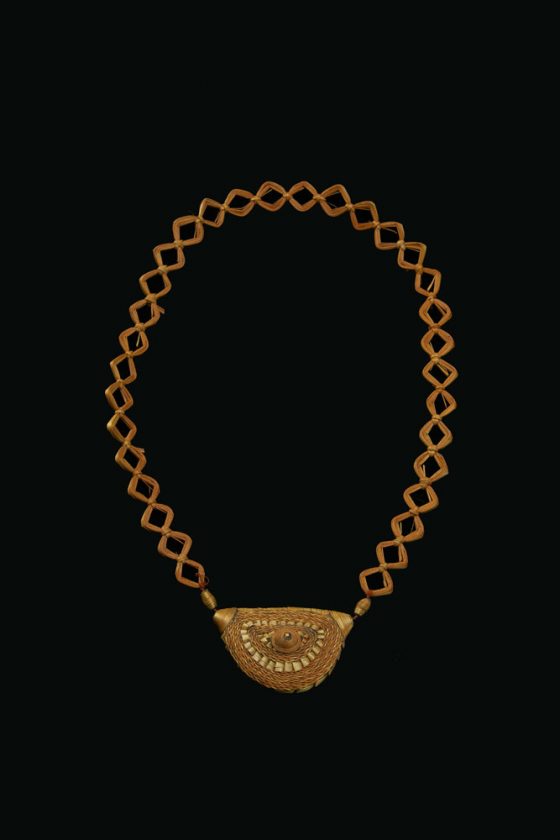

Necklace (bount u sindoné)

Mid-20th century

Gold-plated silver alloy

Gift of Dr. Marian Ashby Johnson, 2012-18-19

Complete perfection. For many Senegalese women the ideal necklace incorporates three pendants—one central component flanked by two complementary, smaller pendants. A string of handmade beads, sometimes with a back pendant attached and worn at the nape of the neck, perfect the ensemble. The central portion of the necklace, known as a kostine, consists of delicate, ornate filigree and requires a great deal of skill and craftsmanship. According to Johnson, this particular style of necklace is a modified form of the kostine known as a bount u sindoné.

Dakar, Senegal

Choker (coloni)

1972

Gold-plated silver alloy

Gift of Dr. Marian Ashby Johnson, 2012-18-21

Enduring. Especially popular with Tukulor women of Senegal during the 1970s and 1990s, the throat ornament on this choker originated among the Peul, Bamana, Songhai, Sarakole, and Wolof communities of Mali, Guinea, and Senegal. The ornament itself may be ancient; a similar form was noted by historian Al-Bakri in the 11th century. It was once worn on a simple leather or fiber cord, but later versions, such as this, are secured by a much more elaborate choker and attest to the longevity and maneuverability of the design.

Goldsmithing Techniques

Creative Reinventions and Alternatives to Gold

In West Africa wearing gold, a scarce and valuable material, demonstrates power and prestige, taste and fashionability. Gold jewelry was often melted down and repurposed to keep pace with the current fashions or sold in times of economic hardship and financial need, functioning something like a mobile savings account. This means that jewelry dated before the mid-20th century is rare. Yet, we can still see the tremendous creativity that took place over just the past century.

Women of lesser means could also show off their fashion sensibility by wearing straw, plaster, or thread-wrapped jewelry. Such alternative materials and methods may predate or mimic the use of gold. In this transposition of material, an ornament once forged in costly metal is cast in more affordable mediums, demonstrating gold’s widespread popularity.