Seen throughout the continent, arts in gold can adorn or distinguish. Gold can embellish wooden sculpture or carry economic value—either in currency as coin or in trade as jewelry. Fashioned into an amulet, gold can embody spiritual devotion or act as the mouthpiece for authoritative communication.

The golden arts of Senegal are less well-known than the famed goldwork of the neighboring nations of Mali, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire. And yet, Senegal too is a burgeoning locale for both historic and contemporary fashion, and its gold jewelry serves as a lens into the unique, lived experience of a fast-paced, cosmopolitan West African experience and identity.

Yamoussoukro or Lacs District, Côte d’Ivoire

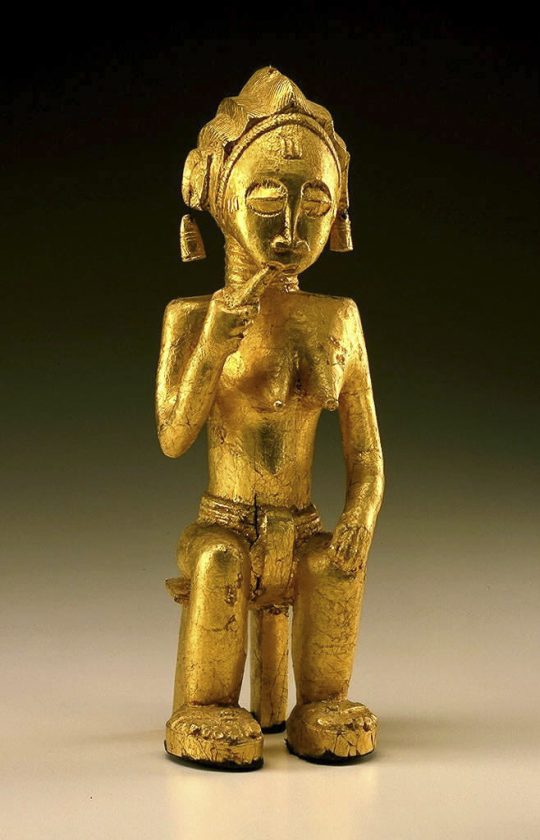

Female figure (sika blawa)

Mid-20th century

Wood, gold leaf

Gift of Philip L. Ravenhill and Judith Timyan, 95-4-1

To commune with the otherworld. Baule artists commonly create wood sculptures. Those covered in thin layers of precious gold (sika blawa) indicate leadership and prestige, and are often displayed at public ceremonies, especially funerals and masquerades. Using a centuries-old technique, a small pellet of gold is repeatedly hammered and turned on an anvil to achieve a uniformly thin sheet of leaf (<1 micron) or foil (>1 micron) before being placed on an ornately carved object and affixed with tiny metal staples or an adhesive.

Mogadishu, Somalia

Armlet with amulet case (dugaagad)

Early to mid-20th century

Gold alloy

Gift of the Loughrans, 76-16-11

To protect. Although silver is the preferred metal in Somalia, gold is still eagerly sought by those who can afford it. This amulet likely contained powerful and protective verses from the Qur’an and was worn by men and women to promote health. When worn by women on ceremonial occasions, however, it also promoted their status.

Golden Opportunities: The Marian Ashby Johnson Collection

Marian Ashby Johnson’s donation to the National Museum of African Art showcases the delicate and refined work of the Wolof and Tukulor goldsmiths of Senegal. Building on extensive fieldwork and interviews starting in the mid-1960s, as well as museum and archival research in London, Chicago, Paris, and Senegal, Johnson assembled a unique collection of jewelry, accompanied by an archive of over 2,000 study images.

Together, they provide an almost encyclopedic overview of Senegalese taste and the role of gold jewelry in Senegal’s cultural, economic, and political history. Johnson’s research looks at the Bambouk goldfields of the Senegal River, documents the techniques, materials, and social class of goldsmiths (teugues), and reveals the inspirational and economic roles of women in commissioning, trading, and fashioning Senegalese jewelry. Johnson’s detailed research and generous gift provide a golden opportunity to understand the breadth and complexity of gold in Senegal.

What Do We Mean When We Say “Gold”?

Gold has long served as a shared global commodity and standard of value. It is one of the softest metals and is extremely resistant to corrosion. When royalty and the elite—those who could afford the purest of gold—first commissioned jewelry, the ratio of gold to alloying component was much higher than what one sees today.

Most of the jewelry in this exhibition is made from a silver or copper alloy, with small amounts of gold present. Because the gold content in these alloys is often not sufficient to achieve the desired golden hue, artists employed gold plate. Called or de Galam in Wolof or or du pays in French, this “country gold” provides maximum flexibility in color (ranging from more yellow to more orange) and accommodates smaller budgets. The most affluent and discerning customers still strive for 14-, 18-, or 22-karat gold whenever possible, though mixtures or silver covered in gold are most common.