When and how did iron smelting and forging technologies emerge in Africa south of the Sahara? Archeologists once thought that knowledge of making iron had arrived in northern Africa by the first millennium BCE, later spreading to the south, but more recent research has pushed the advent of iron production farther back in time.

When and how did iron smelting and forging technologies emerge in Africa south of the Sahara? Archeologists once thought that knowledge of making iron had arrived in northern Africa by the first millennium BCE, later spreading to the south, but more recent research has pushed the advent of iron production farther back in time.

Most contemporary scholars believe that Africans began smelting iron from local ores about 2,500 years ago, but details remain debated. Were these technologies invented and developed in one or several sub-Saharan locales? Were they disseminated with early migrations and trade? However they came to be known to African artisans, iron technologies were quickly adopted and adapted, and large-scale production of iron occurred in several ancient locations. Iron production, use, and exchange defined social and political hierarchies, as confirmed by findings at the archaeological sites of Campo in Cameroon (dating to the 2nd–4th century CE), Kamilamba in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (8th–10th century CE), and Great Zimbabwe (13th–14th century CE).

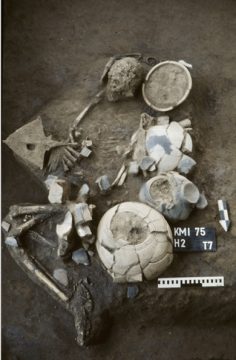

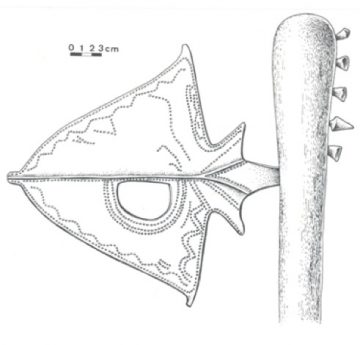

Kamilamba | Tomb 7

Buried evidence. In what is now the heartland of Luba peoples, in southeast Democratic Republic of the Congo, a burial from the 8th to 10th century CE contained a pierced and richly engraved iron axe blade along with pins that likely once decorated its wood shaft. Next to the skull of the buried man was a forged iron anvil. Grave goods at Kamilamba also included pottery, iron tools, and iron and copper jewelry, the latter probably traded from the Katanga Copperbelt to the south. Only a few individuals were buried with rare items such as the ceremonial axe and anvil.

The burial may be an early example of a cultural concept in central Africa that equates kings and blacksmiths. Among Luba living in the region today, anvils are both forging tools and royal regalia. Iron pins resembling those found in the Kamilamba grave are called vinyundo (“little anvils”); they adorn a variety of ritual objects and assure community prosperity through the transformative powers of iron.

Drawing by Yvette Pacquay, 1992

© Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Photographs by Pierre de Maret, Kamilamba, Upemba Region, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 1992

© Pierre de Maret and Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren

Great Zimbabwe

Iron tribute. Today, Great Zimbabwe is the site of the most extensive ruins in Africa south of the Sahara. In the 13th and 14th centuries CE, when it was the principal city of a major state, its population exceeded 10,000 inhabitants. The substantial number of iron hoe blades found together outside the Great Enclosure confirms that locally forged tools enabled agriculture on a scale to feed many thousands. These blade forms were probably also used as currencies. Because no large slag mounds have been found at or near the site, iron production likely occurred throughout the area. This suggests a tribute system through which taxation of small production sites met the demand for iron at Great Zimbabwe.

Photograph by William J. Dewey, 1984

Iron and Cosmologies | Dogon and Mythical Nommo

Mali

Ritual figure

19th century

Iron

Dr. Jan Baptiste Bedaux

Reaching skyward. This unusual form possesses upstretched arms, perhaps asking for rain, and two rings suspended by chains. Dogon smiths forge such figures for placement on shrines or to strike on the ground during ritual acts.

Dogon peoples live in Mali on the remote edge of the Sahara, where farming is precarious due to sandy soil and scarce rains. Their complex philosophical and religious systems help them understand the perils and purposes of life.

Iron and Cosmologies | Bamana Blacksmith Leaders

The stuff of legend. The prominent role of blacksmiths in Bamana society derives from their expertise in ironworking technologies, herbal medicines, and management of relations with the supernatural. Bamana smiths lead the powerful Kòmò initiation association, which teaches its members to marshal exceptional energies called nyama to address the personal, social, and spiritual concerns people face in life. Kòmò encompasses a triangle of power: blacksmith leaders, power objects including masks and altars, and wilderness spirits. Indeed, Kòmò is a daunting thing of the bush, brought into civilized spaces by ironsmiths.

The importance of blacksmiths is stressed in Bamana oral traditions, including the well-known 14th-century Sunjata Epic, which describes the founding of the ancient Empire of Mali (different from today’s republic of Mali).