African mastery of the technical processes of smelting and forging forever changed human civilizations and ushered in new cultural developments. Iron ore is one of the African continent’s most plentiful natural resources, but one of the most difficult to process into usable metal.

African mastery of the technical processes of smelting and forging forever changed human civilizations and ushered in new cultural developments. Iron ore is one of the African continent’s most plentiful natural resources, but one of the most difficult to process into usable metal.

- For blacksmiths’ purposes,

- workable iron must be extracted from iron-rich deposits through a refining process known as smelting. This removes impurities from iron ore by applying intense heat (2100°–2300° Fahrenheit) to separate unwanted mineral contaminants from the iron bound in the rock.

- when heated to a semimolten state in a furnace, iron particles coalesce to form a spongelike and malleable mass called a “bloom.” Iron can then be worked by direct forging, which requires heating it to white-hot temperatures so that it can be shaped by the force of a blacksmith’s hammer and manipulated further with punches, chisels, and other tools.

“Birthing” blooms out of iron ore and objects out of blooms is a “procreative” metaphor used by many African peoples to describe these two transformative processes. Ironworking in Africa is a male-dominated technology that also must involve elements of female power to succeed.

By the 1920s, the majority of indigenous furnaces across Africa had ceased their output of bloomery iron, and iron production was eventually outlawed by all colonial regimes in favor of Western equivalents.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Ceremonial axe

Early 20th century

Wood, iron, copper

Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris, 71.1948.15.29

Expertise visualized. Only a blacksmith with many years of experience and exceptional metal- and woodworking skills could create such a magnificent symbol of authority. In this single work, the artist employed chiseling, punching, inlaying, chasing, engraving, scoring, raising, wrapping, stamping, and embossing, among other techniques. Such a blade added to a blacksmith’s honor and influence in the community, with both owner and artist distinguished every time it was displayed in public.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Figure

17th(?)

Iron, red pigment

Collection of the MAS, Antwerp, Belgium, AE. 0773

Royal work. A masterpiece once kept in the Kuba treasury, this male figure is among the artworks attributed by oral traditions to the renowned blacksmith named Myeel. Remembered for his uncommon skills in forging sculptures and combining iron with copper and other metals, he is believed to have resided at the Kuba royal court in the 17th century. The figure’s most distinctive and prominent features are its hands, each with separate fingers and thumbs meticulously forge welded onto sturdy palms.

Banjeli, German Togoland, 1914

Still from the film Im Deutschen Sudan (1914) by Hans Schomburgk

Forging | The Blacksmith’s Tools

Exceptional expertise. Blacksmiths in Africa, as elsewhere in the world, require four basic tools and a hearth for a fire. With hammers, anvils, tongs, and bellows, they can safely model iron like clay at near molten temperatures.

Tongs and hammers are hand tools designed in a practical range of shapes, weights, and sizes to extend a smith’s reach and multiply his efforts in coaxing iron into shape. He positions his anvil, made of stone or iron, on the ground near the center of his workshop. Sitting within arm’s reach of the anvil, the smith is a quarter turn from his toolkit in one direction and a quarter turn within reach of the forge in the other. The charcoal-fueled fire, well insulated in the floor, is kept alight with forced air vigorously pumped through bellows by a helper.

The site of awe-inspiring technologies still in practice across the continent, the forge itself and the tools and methodologies employed there are characterized by enormous regional diversity.

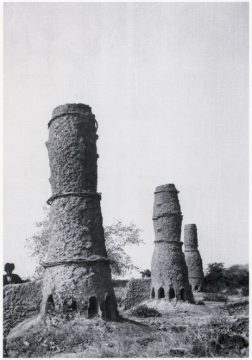

Smelting | From Bloom to Bar

In Hélène Leloup, Dogon Statuary (Strasbourg: Daniele Amez, 1994)

Critical to achieving sufficient smelting temperatures was the selection of slow-growing tree species that provided dense wood for the distillation of long-burning charcoal, but this practice resulted in gradual deforestation. Landscapes with increased sight lines were not easy to defend against conquest by invading armies, and strategic control over iron and resources figured mightily in the political organization of early African communities.