Iron currency tokens are among the most compelling and virtuosic of sub-Saharan blacksmiths’ designs. The shapes of precolonial currency tokens were often derived from blade forms of tools and weapons—so essential was the work accomplished by forged iron objects to local political economies that they were synonymous with value itself. These currency forms stood as payment in the exchanges that mattered most in life: marriage; litigation; ransom of battle captives; and the purchase of horses, enslaved persons, and other prized commodities. Hoe-blade-shaped currencies were created as bridewealth tokens by many African societies, linking agricultural productivity to the reproductive power and labor a wife brings to a household.

Iron currency tokens are among the most compelling and virtuosic of sub-Saharan blacksmiths’ designs. The shapes of precolonial currency tokens were often derived from blade forms of tools and weapons—so essential was the work accomplished by forged iron objects to local political economies that they were synonymous with value itself. These currency forms stood as payment in the exchanges that mattered most in life: marriage; litigation; ransom of battle captives; and the purchase of horses, enslaved persons, and other prized commodities. Hoe-blade-shaped currencies were created as bridewealth tokens by many African societies, linking agricultural productivity to the reproductive power and labor a wife brings to a household.

Currency forms were produced throughout the African continent, most often as bars or blades at sizes suitable to being exchanged in bundles of several or more. Some are dramatic in scale—as tall as a person—and remarkable in design; these drew value from the amount of iron required and from blacksmiths’ forging achievements.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Throwing knife-shaped currency (oshele)

19th century

Iron

Private collection

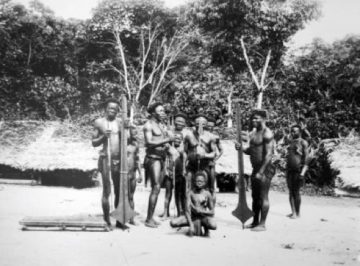

Simply stunning. Oshele were among the most prized possessions of Ndengese and Nkutshu elite. Writing in the early 1920s, the Hungarian ethnographer Emil Torday observed that this tribute token was the highest denomination exchanged within a complex system of metal currencies. Attributed to Nkutshu blacksmiths, these remarkable oshele were traded with neighboring peoples including Ndengese. The smith resolved its intricate design by forging refined bloom into three separate pieces, each with two finely tapered points; the pieces were then forge welded together to attain the currency’s distinctive flared silhouette

Photograph by Emil Torday, British Museum Congo Expedition, Orientale Province, 1907–1909

© RMCA, Tervuren, EP.0.0.11715, Collection RMCA

Tokens of Material Praise

Valuing women. Currencies used as bridewealth constituted material praise of the woman: recognizing her as an individual with life-sustaining capacities. Bridewealth depended upon solidarity among the relatives of the prospective husband and wife. After the two families negotiated the terms of bridewealth, the young man turned to his parents, who then networked with kin to accumulate the goods required. The gifts were amassed in a festive display as testimony to the status of bride and groom and afterwards redistributed, most likely, so that young men of the bride’s lineage could marry.

Euro-African Trade Currencies

Valued exchange. Europeans sought out African-produced iron beginning in the 15th century and later traded imported goods for tools made by African blacksmiths. As of the 17th century, northern European merchants brought bar iron into Africa regularly and in large quantities, hence the commercial term “voyage iron.” This iron was consistently in strong demand along the Upper Guinea Coast (from today’s Republic of Senegal south to the Republic of Liberia), while smelters in interior regions continued to produce their own iron.

By the colonial period, administrators sometimes prohibited local smelting to decrease Africans’ self-sufficiency and increase participation in colonial capitalism. Replicas of coastal communities’ currency tokens were also mass-produced in Europe to destabilize African economies. During the period of the transatlantic slave trade, African smiths were sometimes specifically hunted down, captured, and brought on board ships or to plantations in the Americas for their expertise.