For centuries, tools made from iron have helped Africans forage, hunt, and till the soil, making prosperity possible through efficient and effective management of household and agricultural chores. Knives, hoes, plows, sickles, machetes, axes, and adzes have long been among the blacksmith’s most prolific creations and fundamentally illustrate how sustenance springs forth from the anvil. In particular, short- and long-handled hoes for cultivating and sickles for harvesting have enabled African peoples to survive and thrive. Hoe blade designs and their wooden handle styles vary widely from culture to culture depending upon climate, terrain, soil type, and crop. Handles ergonomically extend strong muscles of backs, shoulders, and arms to the rigors of farming.

For centuries, tools made from iron have helped Africans forage, hunt, and till the soil, making prosperity possible through efficient and effective management of household and agricultural chores. Knives, hoes, plows, sickles, machetes, axes, and adzes have long been among the blacksmith’s most prolific creations and fundamentally illustrate how sustenance springs forth from the anvil. In particular, short- and long-handled hoes for cultivating and sickles for harvesting have enabled African peoples to survive and thrive. Hoe blade designs and their wooden handle styles vary widely from culture to culture depending upon climate, terrain, soil type, and crop. Handles ergonomically extend strong muscles of backs, shoulders, and arms to the rigors of farming.

Essential to labor, family, and community life, iron tools have also been rendered into objects of social and economic status with sacred meanings and ritual efficacies. Hoe blades on ceremonial objects, for example, work in tandem with sculpted figural elements to promote fertility and guarantee survival. Other forged iron items are deployed to encourage life-giving rains or to signal the social passages that assure human continuity. Their positive capacities as objects of utility, meaning, and metaphor result from the transformation of iron by blacksmiths.

Hoes of Authority and Prosperity

Beyond farming. After the knife, no tool is more essential than the hoe, given its importance to the cultivation of crops throughout Africa. Blacksmiths in many cultures frequently transform hoe blades into ritual objects used to communicate authority and to assure agricultural abundance. Yorùbá peoples from Nigeria, for example, express this in impressive staffs, such as the one displayed nearby, used to seek blessings from the fertility deity Oko. The efficacy of such staffs is ensured because they are forged from blades worn down by farmers over years of providing for their families.

Iron as Activator of Rain and Fertility

Imploring with iron. In parts of Africa, iron is considered particularly potent as offerings made to secure seasonal rains and bring bountiful harvests. Mumuye peoples of Nigeria’s Middle Benue river region recognize rainmakers as powerful protectors of community survival. Rainmakers’ ritual supplications require zigzag-shaped forged iron wands used singly or in bundles of upward thrusting wavy branches. Their energetic shapes recall flashes of lightning or the sudden movement of slithering snakes, both thought to presage rain. They also evoke rivulets or even torrents of water on parched land. Rainmakers secure the wands in the ground, where, as visual petitions made of iron, they marshal the earth’s life force.

Nigeria

Vessel with rainmaking wands

Mid-20th century

Iron, ceramic

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X2008.32.3, museum purchase, 2008

Containing power. To become vertical, these iron rainmaking wands were likely impaled in soft clay inside the ceramic vessel before it was fired. The bump-covered surface of the pot and its fire-born contents signal ritual purpose and potency.

Forging Life’s Passages

Transitions and transformations. Ironworking is vital to the regional economies of peoples living in the Mandara Mountains in northern Cameroon and the adjacent Gongola River Valley of northeastern Nigeria. During coming-of-age ceremonies, iron adornments worn by young men and women connect their physical and social changes to the transformative processes of smelters and blacksmiths. Extravagant forms of iron accoutrements, held as dance staffs or worn, also mark the transition from adulthood to death (and ancestor status). The use of iron implements in agriculture, hunting, and, formerly, warfare was likely the basis for employing such forms as ritual objects to announce and activate social and spiritual passages.

Nigeria

Ritual sickle (wanshipta)

Mid-20th century

Iron

Fowler Museum at UCLA, X2008.16.1, museum purchase

Marking transitions. Ga’anda iron dance staffs were held aloft during pre-burial rituals, marking the final passage to death. Their form combines the curvature of a long-handled sickle with the flair of an axe blade; a crown of spikes may have symbolically protected the deceased as he or she passed to the world of the ancestors. Finely chiseled triangular designs on the surface repeat the scarification patterns inscribed in the skin of Ga’anda girls upon their transition into adulthood and marriageability.

Elegance in Iron

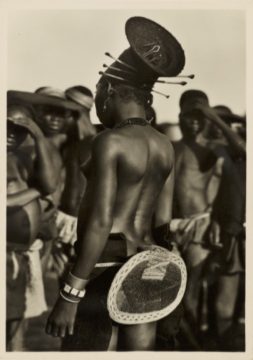

Belgian Congo (Democratic Republic of the Congo)

Photograph by Casimir d’Ostoja Zagourski,

c. 1926–37

Casimir Zagourski Photographs, c. 1925

EEPA 1987-024-4053, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution

Hair ornaments, necklaces, bracelets, headdresses, and belts temporarily enhance the body. In the Congo, men and women once wore their hair shaped, teased, and braided into elaborate coiffures held in place and embellished with delicately forged iron hairpins fashioned with pointed ends that helped the styling process.

More permanent bodily transformations, such as scarification, were achieved with small iron blades that made precise incisions that healed into patterns of raised bumps or lines. Thin-edged razors have also been used by men for head and facial shaving, sometimes in patterns prescribed for ceremonial occasions.

As documented in photographs from the past century, these forms of body decorations are historically part of localized and culturally specific systems of beautification.