How do you find the key visual details that reveal many different stories about Africa’s arts?

The best African art rewards close examination with new, surprising features that may not have been apparent at first glance. Through the objects before you, African artists have expressed a wealth of different stories—personal dramas, religious enlightenment, political histories, among them. Look for details like color and pattern, gesture and expression, proportion, scale, materials, and style, and learn to see as artists do. When you do, whole new stories—and the worlds they depict—may emerge.

Power is the ability . . . to tell the story of another person. . . . When we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise.

—Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Bété artist

Bas-Sassandra District, Côte d’Ivoire

Face mask (n’gre)

Late 19th century

Wood, metal, cloth, cowrie shells

33.5 x 22.8 x 17.2 cm (13 3/16 x 9 x 6 3/4 in.)

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Brian Leyden and museum purchase, 2013-21-1

EXPRESSION | Garish glare. Imagine these large, projecting eyes glaring at you from underneath the massive, furrowed brow. What message is that open, gaping mouth trying to convey?

This Bété mask is deliberately unsettling. Embodying powerful spiritual forces associated with the forest, it may have appeared among Bété communities to settle disputes, or to lead battles. Its expression is one of political power won by coercion and disruption.

Bright Bimpong

b. 1960, Takoradi, Western Region, Ghana

Works in Lawrenceville, N.J.

Efo II

1993

Iron

44 x 20.6 x 20.7 cm (17 5/16 x 8 1/8 x 8 1/8 in.)

Museum purchase, 2001-3-1

SCALE | Little big man. Nothing about the monumental stance, or girth, of this man appears small. Even the gesture of leaning back and grasping hands behind his back seems to expand his presence, perhaps even his ego. A “big man” typically has a grandiose self-image, often accompanying outsized political and economic influence.

At this size, what might the artist be suggesting about the role of such men in society?

Kongo artist

Kongo Central Province, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Staff (mvwala amfumu)

19th century

Ivory, wood, metal, ceramic

78.5 x 11 x 10.2 cm (30 7/8 x 4 5/16 x 4 in.)

Gift of Walt Disney World Co., a subsidiary of The Walt Disney Company, 2005-6-32

MATERIALS | A hierarchy of value. This staff, a symbol of a Kongo ruler’s capacity to affect events in both the realms of the everyday and the beyond, presents an ordered progression of valuable materials. Imported white ceramic, a most rare and precious item, forms the woman’s eyes. Lustrously red-tinged elephant ivory—a valuable, but less rare commodity in 19th-century Congo than today—comes next, forming the woman’s body. Metal, either imported or forged and hammered at considerable effort, follows. Its partially broken shaft is made of the most widely available and functional material, wood.

Owusu-Ankomah (Kwesi Owusu-Ankomah)

b. 1956, Sekondi, Western Region, Ghana

Works in Bremen, Germany

Off My Back

1995

Acrylic on canvas

157.1 x 211.7 x 4.1 cm (61 7/8 x 83 3/8 x 1 5/8 in.)

Museum purchase, 2000-17-1

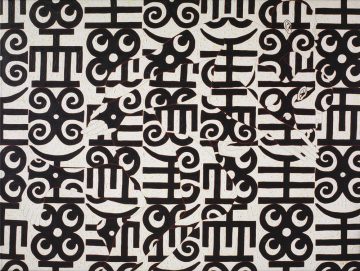

PATTERN | Playing with perception. Can you find the figures hidden in this work? Owusu-Ankomah creates abstract patterns from the symbolic sign system known as adinkra used in Ghana, the country of his birth. The adinkra patterns create an environment in which the artist plays with our perception, as figures disappear and reemerge from the canvas.

Adinkra is a stamp technique used in Akan funerary cloths. Each symbol represents a particular proverb and set of interpretations. Both men in this painting are covered in, and emerge from, this universe of meaning. The painting’s predominant adinkra motif is a double ram’s horns, a symbol that suggests that when two rams lock horns in struggle, one must give way.

What is the relationship between the two men and their surroundings?