Caravans of Gold home | Saharan Echoes | Driving Desires: Gold and Salt | The Long Reach of the Sahara |

Archaeological Imagination Station: Giving Context to Fragments / Hi Videos | Saharan Frontiers | Shifting Away from the Sahara | Teachers Guide

Subsection: Tour the Caravans of Gold World

________________________________________

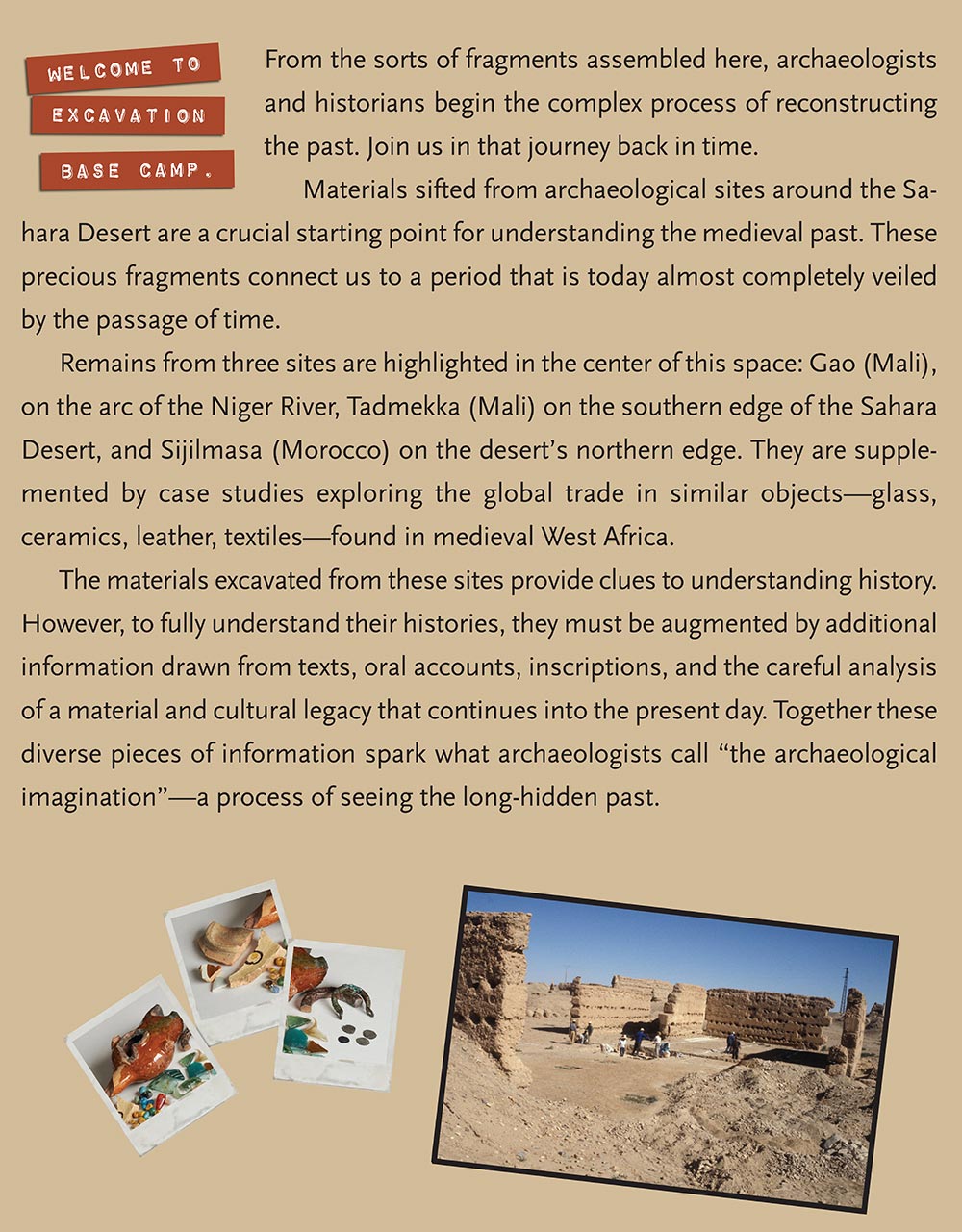

Investigator Interviews: Excavating Gao, Tadmekka, and Sijilmasa

Case Study: Some of Africa’s Oldest Textiles

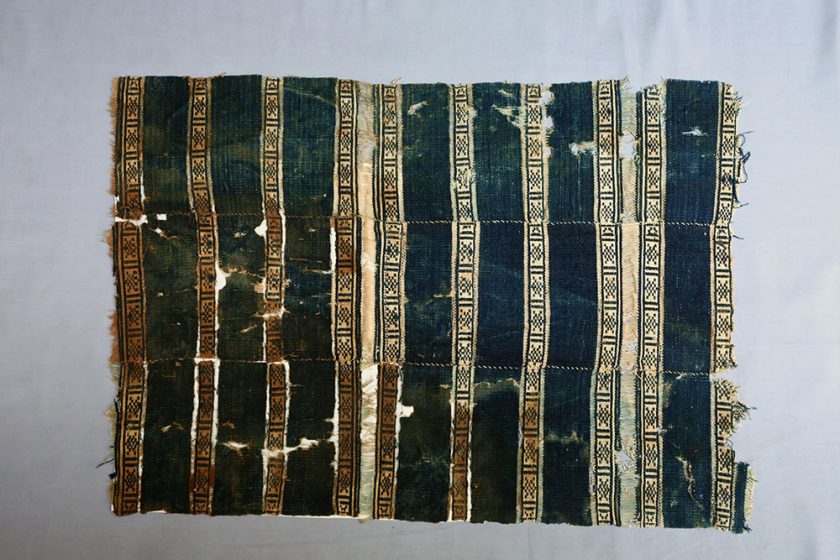

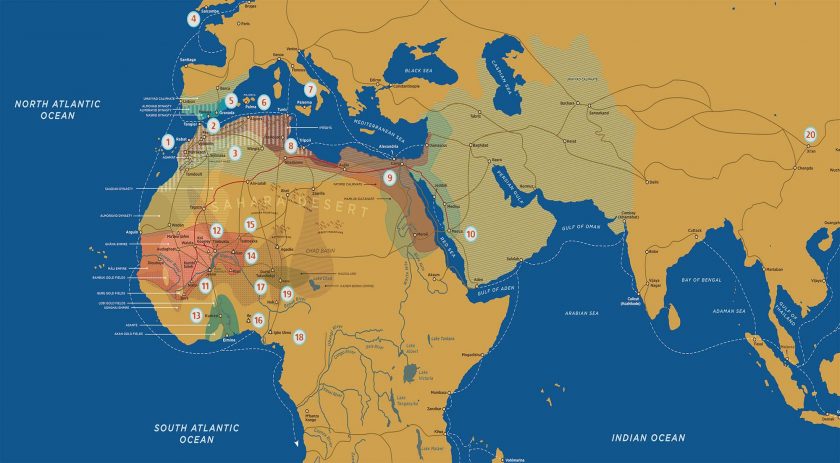

In the 1960s and 1970s, archaeologists excavated more than 500 fragments of woven cotton and wool textiles from caves in Mali’s Bandiagara Escarpment, a massive group of cliffs east of the Inland Niger Delta. The caves were used as burial sites during the medieval period, and the textiles were among grave goods that also included ceramic vessels, tools, weapons, and ritual objects. Known as the Tellem Textiles, named for the peoples who lived in the region at that time, they are among the oldest surviving textiles from West Africa.

The earliest of these precious fragments date to the 11th century C.E. They display a variety of weaving and dyeing techniques that point to a deeply rooted regional weaving tradition. The structures and patterns of the fragments resemble textiles woven by the Fulani and Mande weavers in more recent eras, suggesting connections with populations who lived closer to the centers of trans-Saharan trade.

The textiles are composed of narrow strips sewn together edge to edge to make a larger cloth. Cotton was widely cultivated in the Western Sudan, but indigo dye was imported from north of the Sahara, while sheep’s wool came from the region of Mauretania to the northwest.

Exacavated at Sijilmasa, Drâa-Tafilalet Region, Morocco

Inscribed vase

11th century C.E.

Musée archéologique de Rabat, Rabat, Morocco

Egypt or Syria

Bowl

11th century C.E.

Luster-painted fritware

Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, Canada, AKM684

Remains from copper working have been uncovered at sites in present-day Mali including Gao, Jenne, and Tadmekka. Copper was worked in its pure state or alloyed with arsenic, lead, tin, or zinc to make brass—the yellow tones of which might have been particularly appreciated because of their visual affinity with gold.

This large openwork copper alloy disk was excavated at Gao’s royal capital, Gao Ancien; its blue-green color is the result of corrosion over many centuries. The smaller copper alloy fittings were excavated at the major trading center of Tadmekka. One of them has a small piece of hide adhered to it, providing some evidence of its former use.

The large Tuareg shield was made in the early 20th century C.E. Crafted of oryx hide and embellished with copper disks and colored hide and cloth, it alludes to one possible use of copper-alloy decorations in the medieval period.

Oryx hide shields were traded across the Sahara Desert. The 12th-century C.E. Granadan geographer Mohammed ibn Abu Bakr al-Zuhri noted, “these shields are most amazing . . . given as presents to the kings of the Maghrib and al-Andalus.” Similar shields are depicted in the Cantigas de Santa María, a 13th-century C.E. Spanish manuscript of an Almohad army in battle against the king of Marrakech, who carries the Banner of Mary.

The commodities and manufactured goods that moved along trans-Saharan trade routes were often destined for markets at astonishing distances from their places of origin. A small fragment of celadon porcelain that was excavated at the site of Tadmekka, Mali, is a type known as Qingbai ware. Produced in southeastern China, Qingbai pottery was widely exported between the 10th and 12th centuries C.E., and was exchanged along routes in a process called relay trade. Fragments of Qingbai ware have been found at medieval sites from Central Asia to Egypt, and across the Sahara.

The shape of this fragment suggests that it once formed part of the rim of a bowl. The distinctive damask weave of a small piece of silk, also excavated at Tadmekka, proves that it was also made by Chinese artists, though the chain-stitch embroidery in red cotton that runs across it was likely added in Tadmekka as further embellishment to a luxury garment.

Tour the Caravans of Gold World

Click here to join curator Kevin D. Dumouchelle on a video tour of key sites covered by the exhibition.