Caravans of Gold home | Saharan Echoes | Driving Desires: Gold and Salt | The Long Reach of the Sahara |

Archaeological Imagination Station: Giving Context to Fragments / Hi Videos | Saharan Frontiers | Shifting Away from the Sahara | Teachers Guide | Virtual First Look

________________________________________

The creation of new trading centers along the West African coast slowed but did not wholly end trans-Saharan trade. New intermediaries, like the Asante Empire (in central Ghana) benefitted from their role as connectors between the Sahara and the Atlantic. In Asante, the legacy of the Saharan gold trade continued—particularly in the systems of measure based on the mithqal (4.5 grams) that were used to weigh gold—the lifeblood of the empire.

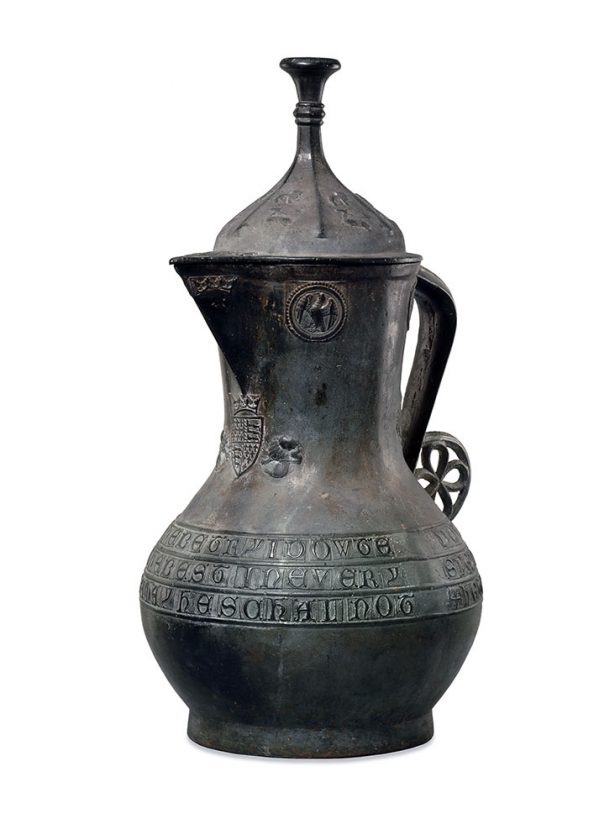

Manufactured in England

Found at Manhyia Palace, Kumasi, Ashanti Region, Ghana

The Asante Jug (Richard II Ewer)

1390–99 C.E.

Copper alloy

The British Museum, London, England, 1896,0727.1

Cosmopolitan Asante | The asantehene (king) maintained a museum in his palace in Kumasi in which he could display these sorts of exotic curiosities. This ewer might have traveled across Saharan trade routes soon after it was made, or it might have been imported to Asante at a later time through trade along the Atlantic coast.

Made in England in the 14th century C.E., it is embellished with heraldic motifs and Lombardic inscriptions. The royal arms of England on the front of the jug reference the reigns of both Edward III and Richard II, but the badges on the lid depicting a stag indicate that it was produced during Richard’s reign, specifically between 1390 and 1400 C.E. It was taken by the British from Kumasi, in 1896 C.E.—the last in that century’s multiple British raids on their Asante rivals.

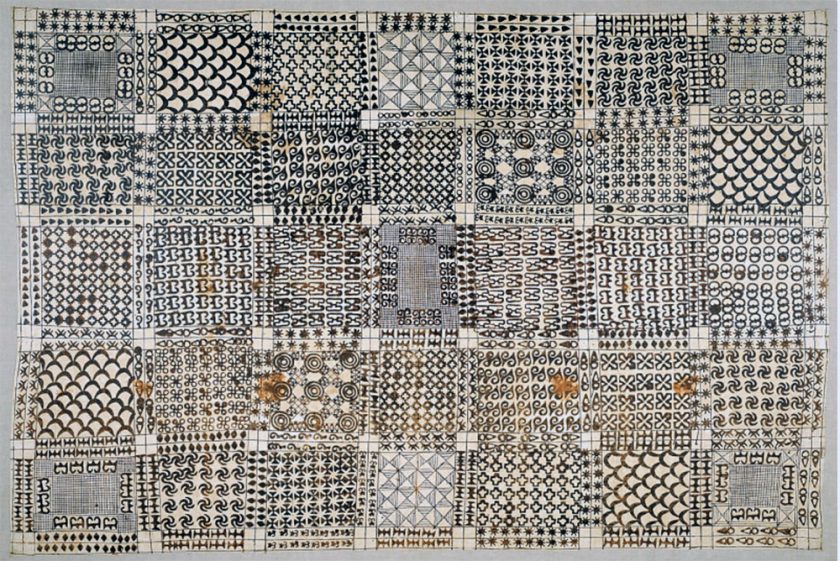

Ashanti Region, Ghana

Adinkra (wrapper) owned by Asantehene Prempeh I

Before 1896 C.E.

Imported cotton cloth, black pigment

National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, museum purchase, 83-3-8

Dressing to Resist | Historically Asante royalty wore adinkra, large wrappers with stamped patterns, only during periods of mourning. The cloths are hand-stamped with a range of visual patterns, each representing a proverb or characteristic. Some adinkra sign systems may have their origins in the use of Islamic script and talismans by specialists at the king’s court. The term adinkra means “to employ or make use of” or “a message.” It also connotes separation or leave taking.

This cloth was worn by Asantehene (king) Prempeh I on the day the British deposed him in January 1896. Prempeh had successfully resisted British demands to relinquish Asante sovereignty for several years, but British demands for control of the region prompted them to sack and invade the capital, Kumasi. Prempeh and his followers were arrested and exiled. By wearing this cloth in his last appearance before his people for 28 years, Prempeh left the Asante people with two key visual messages—decrying the unlawful British invasion, while retaining his rights and status as king.

Manufactured in North Africa

Found at Salcombe Cannon Site, Devon, England

Fragment of a clasp and pendant

Gold

The British Museum, London, England, 1999,1207.474 and 1999,1207.469

All the Way to England | In 1992 a shipwreck was discovered off the coast of Devon, England. The ship sank in the mid-17th century C.E., and its cargo included more than 400 gold coins, most of them minted in Morocco, as well as North African gold ingots and jewelry. Mostly worn and broken, these gold objects were on their way to be melted down and repurposed by the British Crown.

Today, these rare items provide a glimpse into late medieval North African goldwork. The fragment of a clasp is among the earliest surviving examples of a form—the fibula—that has become an iconic symbol of Saharan jewelry.

Struck at London

Gold

The American Numismatic Society, New York, NY, 1957.172.19. and 0000.999.596

5 Guinea Coin of James II

1685 C.E.

1 Guinea Coin of James II

1688 C.E.

King in his (Elephant-and-) Castle | The Dutch and English vied for lucrative trade along Africa’s West Coast in the mid-17th century C.E. In this period the English produced guinea coins marked with an elephant-and-castle motif below a bust of the English king, James II. The motif was stamped only onto coins made from West African gold acquired by the newly established Royal Africa Company, which was granted monopoly on this trade by the British crown in 1672. It illustrates the lasting importance of gold and ivory as commodities, even as trade shifted away from the Saharan routes.