Caravans of Gold home | Saharan Echoes | Driving Desires: Gold and Salt | The Long Reach of the Sahara |

Archaeological Imagination Station: Giving Context to Fragments / Hi Videos | Saharan Frontiers | Shifting Away from the Sahara | Teachers Guide

Subsections: Arabic Accounts of West Africa | Slavery in the Medieval Western Sudan | Mansa Musa at the Crossroads

__________________________

Sahara at Center The medieval Sahara was at the center of an interconnected and far-reaching trade network that extended in multiple directions. It was a hub of exchange—in goods, people, and ideas—that was at the heart of medieval global history.

Intermediaries were essential to trade across the Sahara. Diverse peoples, each with their own language, perspective, system of supply and demand, resources, and expertise, contributed to maintaining the connections that supported far-reaching networks of exchange. These included North African Muslims who spoke Arabic and followed Islamic laws governing trade. Amazigh (Berber) nomads, likewise competent in Arabic, were essential for their knowledge of the routes across the desert and for their expertise in managing the long camel caravans that were the most efficient way to traverse this challenging environment. South of the desert, they interacted with Wangara merchants who traveled among the diverse peoples of Africa’s Western Sudan region, spoke their languages, and navigated long-standing trade routes along the Niger River and its tributaries.

Djenné, Mopti Region, Mali

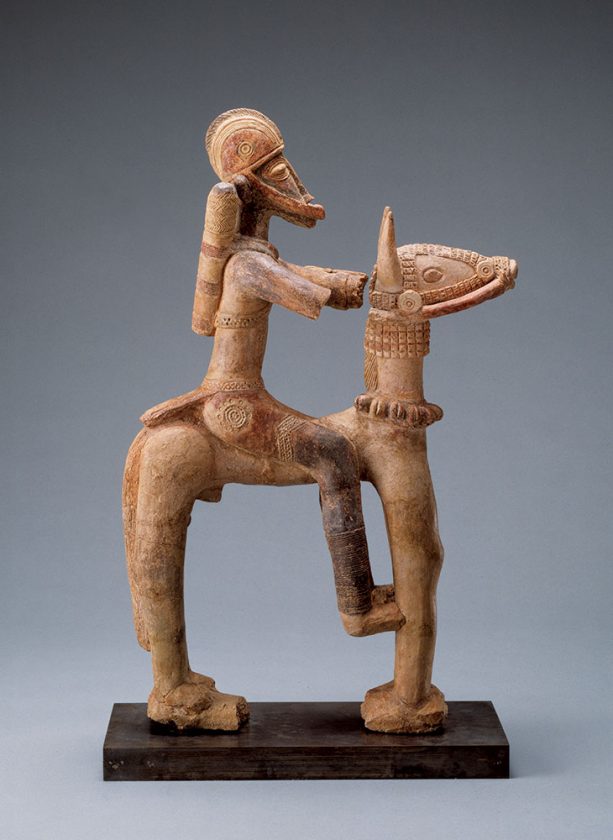

Equestrian figure

13th to 15th century C.E.

Ceramic

National Museum of African Art, museum purchase, 86-12-2

Riding into History | The elaborate dress of this figure suggests ceremonial military attire; it may represent a warrior who was once at the command of Sundjata Keita (c. 1210–55 C.E.), founder of the Māli Empire, and one of Mansa Musa’s predecessors.

Since the 1940s, low-fired ceramic figures and fragments such as this have been unearthed at various sites throughout the Inland Niger Delta region, an area that developed urban centers as early as the fourth century C.E. Research, including local oral traditions, indicates that all ethnic groups in the Delta region used these figures. The earliest known written reference to them occurs in a letter of 1447 C.E. In it, a visiting Italian merchant remarked that the figures were kept in sanctuaries and venerated as representing the deified ancestors of famous founding rulers of the region.

Bankoni, Bamako Region, Mali

Horse and rider and four figures

14th to 15th century C.E.

Terracotta

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Ada Turnbull Hertle Endowment, 1987.314.1–5

To Arms | A knife blade was excavated at the medieval trading center of Tadmekka, Mali. Sheathed knives are also depicted worn strapped to the upper left arms of medieval terracotta figures. The figures are portrayed wearing bangles, hair ornaments, and pendants that reflect the wealth of the region, which was heavily involved in trans-Saharan exchange.

Horsemen—a common theme—point to the importance of cavalry for territorial expansion and security. A breed of small horses was indigenous to the region, and larger Arabian horses were also imported across the Sahara. This group of figures relates stylistically to others that were excavated from mounds near Bamako, Mali’s capital, where they had been intentionally buried.

Natamatao, Mopti Region, Mali

Kneeling figure

12th to 14th century C.E.

Terracotta

Musée national du Mali, Bamako, Mali, 90-25-10

Taking It with Them | The medieval site of Natamatao, in the Inland Niger Delta, includes the remains of a town and a nearby burial ground where terracotta figures were interred alongside the skeletons of horses and humans. The Niger River’s fertile delta supported thriving cities in the medieval era, nurturing more than 60 interdependent communities. At Natamatao, excavations unearthed materials associated with trans-Saharan trade, notably a bundle of imported copper ingots. Bracelets and pendants, like those depicted on the kneeling figure, might have been made of brass, a copper alloy. The depiction of horses likewise points to commerce, as they were traded across the Sahara.

Egypt or Syria

Biconical bead

11th century C.E.

Gold

Aga Khan Museum, Toronto, Canada, AKM618

The Form Endures | The wealthy and powerful Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171 C.E.) was active in Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, and trans-Saharan trade networks. This bead is composed of two filigree cones that are joined along a central seam, a still contemporary bead shape that has its origins in antiquity.

Senegal

Biconical bead

19th to early 20th century C.E.

Gilded silver

The Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI, Founders Society Purchase, Eleanor Clay Ford Fund for African Art, 77.10

Reinventing the Past | It is likely that the biconical bead form traveled across the Sahara to West Africa in the medieval period. Small terracotta beads with the distinctive biconical shape were made at Gao Saney; more extravagant gold beads, like the medieval Fatimid one, were likely brought across the desert as personal possessions or diplomatic gifts.

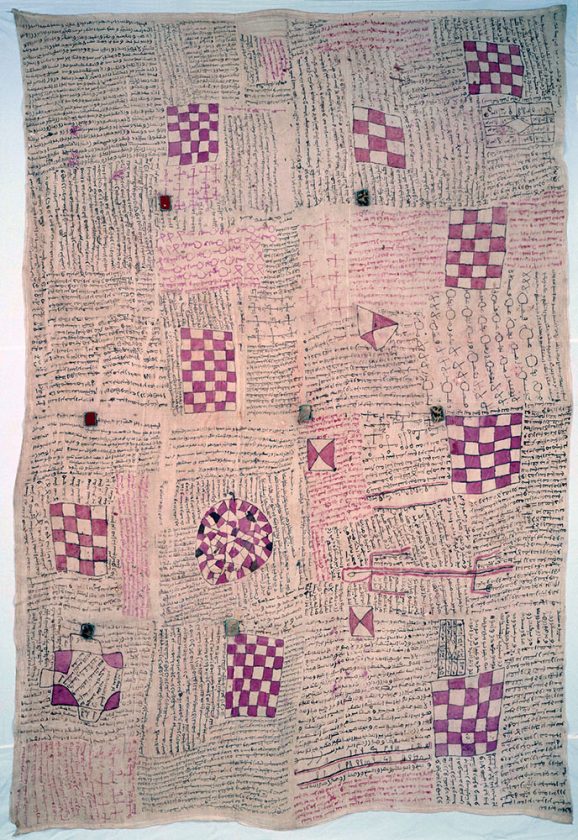

Probably Senegal

Talismanic textile

Late 19th or early 20th century C.E.

Four panels joined: cotton, plain weave; painted; amulets of animal

hide and felt attached by knotted strips of leather

The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, African and Amerindian Purchase Fund, 2000.326

Healing Words | The Qur’anic passages written across this textile and contained in the amulets attached to it have therapeutic intent. Leather-encased amulets are also worn on the body in the form of necklaces and other items of adornment. The activation of the words of the Qur’an for protection and healing is a widespread Islamic practice.

Arabic Accounts of West Africa

In addition to its role as a conduit for goods and people, the Sahara was also connected by ideas. Scholars on both sides of the desert built a common intellectual tradition linked by a shared faith—Islam.

Diplomats, geographers, historians, and travelers of the era wrote medieval Arabic accounts of the Bilad al-Sudan, the “land of the Blacks.” This literature is challenging to interpret, as its authors frequently drew from second- or third-hand reports. Nonetheless, when viewed in conjunction with the material record, these accounts can provide valuable information.

For instance, in composing his Book of Routes and Realms, the 11th-century C.E. Andalusian scholar al-Bakri combed through existing literature, which he enriched with information he garnered from travelers. The book, which has been copied many times throughout the centuries since its first appearance, describes trade across the Sahara Desert and includes early mentions of towns including Sijilmasa, Gao, and Tadmekka.

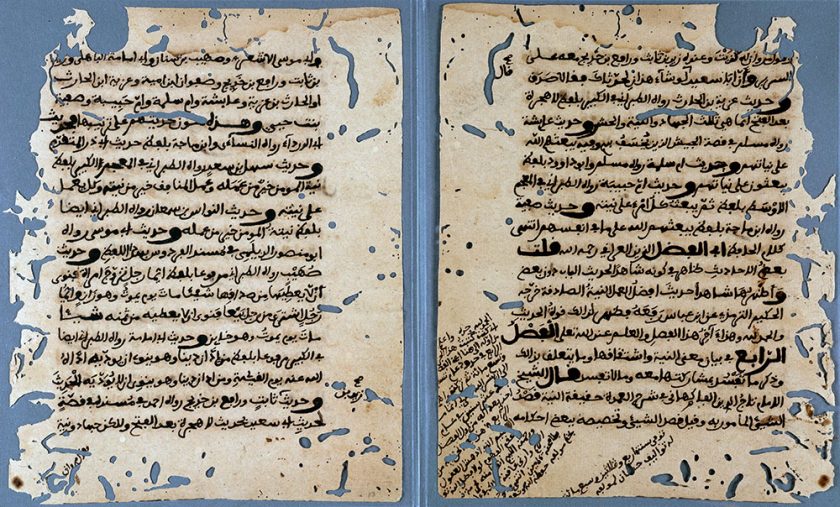

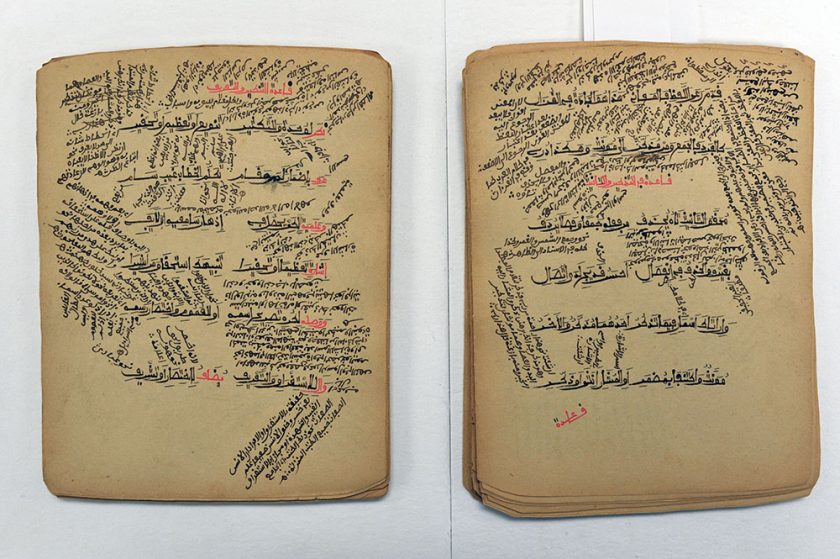

1556–1627, b. Araouane, Mali

Worked in Timbuktu as dictated to Yusuf al-Isi

Ghayat al-amal fi tafdil al-niyya ’ali al-’amal (The Uttermost Hope in the Preference of Sincere Intention over Action)

1592 C.E.

Ink on paper

Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, Hunwick 541

Nigeria

Miftah li’l tafsir (Commentary on the Qur’an)

1794–95 C.E.

Black and red ink on paper

Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, Paden 248

Centuries of Learning | As Arabic spread across the Western Sudan, a significant and original tradition of scholarship developed. The treatise on ethics by the learned scholar and religious leader Ahmad Baba is among the oldest surviving Arabic manuscripts from West Africa. A member of one of Timbuktu’s earliest scholarly lineages, Ahmad Baba composed more than 60 works, including a ground-breaking fatwa, or legal opinion, on slavery. The treatise by ’Abd Allah bin Fudi, the brother of the 18th-century religious and political leader Usman Dan Fodio, offers commentary on the Qur’an.

Slavery in the Medieval Western Sudan

Both Christian and Muslim teachings in the medieval period were used to justify the enslavement of “non-believers.” In justifying the Crusades and state-building across the linked “seas of gold” of the Mediterranean and the Sahara, these cynical statements by popes and scholars alike had the net effect of slowly dehumanizing peoples connected by centuries of exchange, yet divided by faiths.

Medieval Arabic accounts reveal facets of Saharan exchange that are not apparent in the archaeological record. This is particularly true of slavery, which is made visible almost uniquely in these written accounts.

In the medieval period, enslaved West Africans, predominantly women and children, were first taken to Morocco and then eastward to Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and beyond. Captured individuals were forced to make the harrowing trek on foot across the Sahara, and many died during the journey.

Some scholars have argued that high-profile events, like Mansa Musa’s celebrated pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 C.E., may have inadvertently contributed to growing European perceptions of West Africa as a source of unimaginable wealth of all kinds. Gold and material resources were certainly in evidence but—accompanied as Musa was by thousands of enslaved peoples—so too emerged the suggestion of West Africa as a source of forced labor.

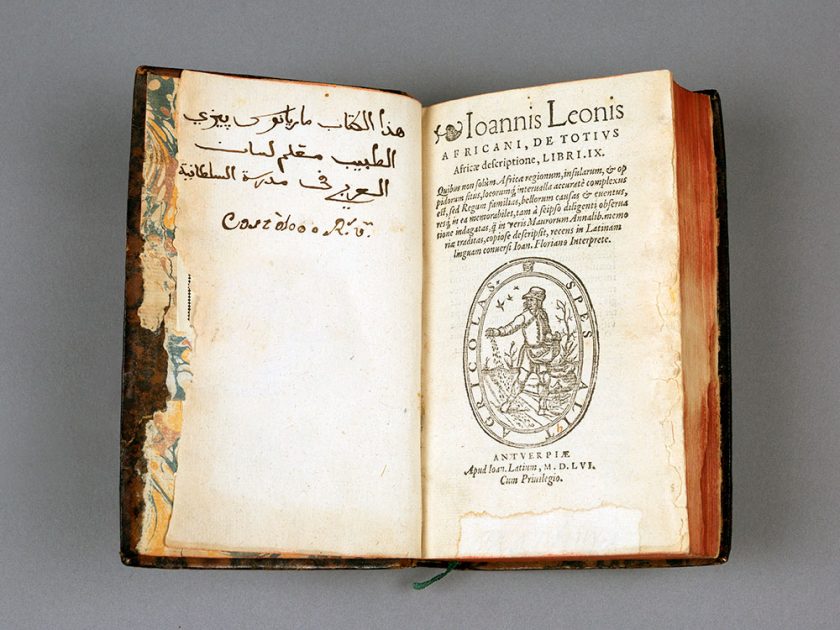

c. 1492–1550, b. Grenada, Emirate of Granada [Spain]De totius Africae descriptio (Description of Africa)

Antwerp, Spanish Netherlands

1556

Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, 916 L576.2

Best Seller | Imprisoned in Rome for nine years by order of the pope, the writer known as Leo Africanus completed his Description of Africa in 1526. He was born in Grenada in the final days of Islamic rule in the Spanish peninsula, moving first to Fès, Morocco. From there he traveled widely as a diplomat and scholar, including to Cairo and across the Sahara to Timbuktu.

The book, composed in Italian, was the first description of Africa published in Europe for a largely European and Christian readership hungry to know more about the continent’s geography, people, and resources.

Mansa Musa at the Crossroads

The 14th-century C.E. ruler of the Māli Empire, Mansa Musa, was immensely wealthy and powerful. He controlled a territory that included the Bambuk and Bure gold fields, the Sahara Desert’s southern fringe, and the upper and middle Niger River. Musa made full use of his empire’s strategic location at the crossroads of these major zones of trade.

In 1324 Musa embarked on the hajj, the religious pilgrimage to Mecca that all Muslims are encouraged to make in their lifetime. It was also an opportunity to forge alliances and to advertise his wealth and power through lavish displays. According to the scholar Shihab al-’Umari, who interviewed residents of Cairo present at the time of Musa’s visit, “this man flooded Cairo with his benefactions. He left no court emir nor holder of a royal office without the gift of a load of gold. . . . They spent gold until they depressed its value in Egypt and caused its price to fall.”

Al-’Umari also describes the sumptuous diplomatic gifts that Musa received during his stay in Cairo:

The sultan sent to him several complete suits of honor for himself, his courtiers, and all those who had come with him, and saddles and bridled horses for himself and his chief courtiers. His robe of honor consisted of an Alexandrian open-fronted cloak embellished with . . . cloth containing much gold thread and miniver fur, bordered with beaver fur and embroidered with metallic thread, along with golden fastenings, a silken skull-cap with caliphal emblems, a gold inlaid belt, a damascened sword, and a kerchief embroidered with pure gold.

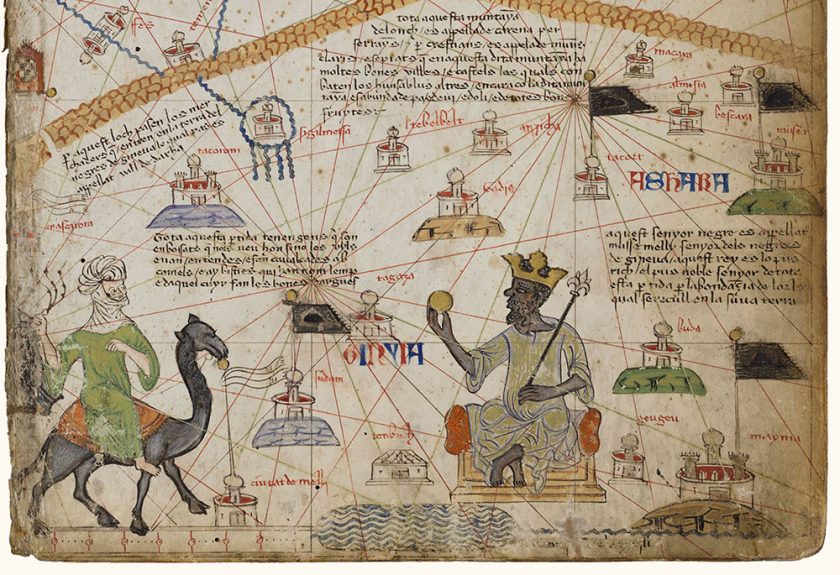

Mansa Musa’s renown was so widespread that 50 years after his pilgrimage he was prominently portrayed wearing a golden crown and grasping a large gold orb and scepter on a world map created on the Mediterranean island of Majorca.

1325–1387 C.E., b. Palma, Majorca, Spain

Worked in Palma, Majorca)

Catalan Atlas (reproduction)

Illuminated parchment mounted on six wooden panels

Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Ms. Espagnol 30

Seeing the Medieval World | Made as a gift for Charles V, the king of France, and possibly drawn by the Jewish cartographer Abraham Cresques, the map known as the Catalan Atlas was a showcase of state-of-the-art mapmaking in the 14th century C.E. The prominent portrait of Mansa Musa, the emperor of Māli, on the second panel attests to the importance of West African gold in the medieval global economy.

The caption explains: “This Moorish ruler is named Musse Melly [Mansa Musa], lord of the Negroes of Guinea. This king is the richest and most distinguished ruler of this whole region on account of the great quantity of gold that is found in his lands.”

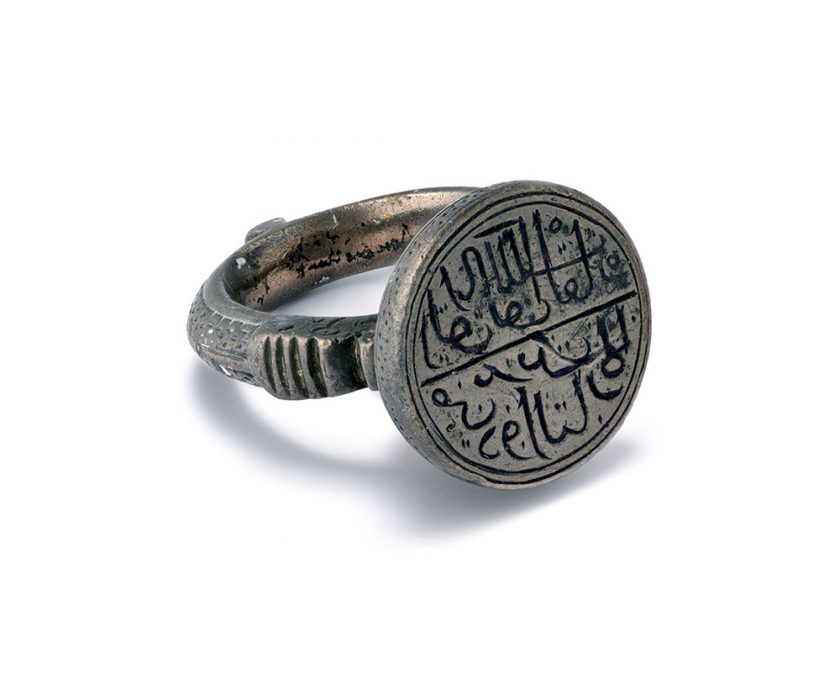

Iran

Signet ring

15th to 16th century C.E.

Silver

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, The Nasli M. Heeramaneck Collection, gift of Joan Palevsky, M.73.5.336

Tools to Rule | A sword and jewelry were also among the diplomatic gifts received by Mansa Musa during his pilgrimage.

The historian and geographer Abu ’Ubayd al-Bakri (died 1094) provided information about the Saharan caravan trade to a readership hungry to learn about faraway trading partners. In his Book of Routes and Realms, published in 1063, al-Bakri describes royal succession in Kawkaw (present-day Gao): “When a king ascends the throne, he is handed a signet ring, a sword, and a copy of the Qur’an.”

Egypt

Cap

14th century C.E.

Silk

The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio, purchase from the John L. Severance Fund

1950.510

For a Brother in Faith | During his sojourn in Cairo, Mansa Musa was received by the sultan al-Nasir al-Din Muhammad, who showered him with gifts including a skullcap with emblems connected to the sultan’s reign. The cap undoubtedly resembled this one, which is quilted for extra warmth.

The imagery on this cap alternates between animals of the hunt and the name al-Nasir Muhammed ibn Qala’un.

Spain or North Africa

Astrolabe

1236–37 C.E.

Brass

Courtesy of Adler Planetarium, Chicago, IL, A-71

Guided by the Stars | Mansa Musa would have encountered, and possibly employed, this type of object on his pilgrimage to Mecca across the Islamic lands.

Astrolabes served many functions in the Islamic world. These highly sophisticated instruments were used to wayfind, tell time, survey land, and verify the direction of Mecca, which Muslims face when praying. The astrolabe was also used to calculate the relative position of stars and planets.

Mauritania

Ornaments

20th century C.E.

Gold alloy

National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, gift of the Roy and Brigitta Mitchell Collection, 2010-10-2

Radiant Traditions | The 14th-century C.E. Syrian scholar Shihab al-’Umari described the golden regalia at the medieval court of Mansa Musa, the ruler of Māli: “Their brave cavaliers wear golden bracelets. Those whose knightly valor is greater wear gold necklaces also. If it is greater still, they add gold anklets.” Little physically remains of such extraordinary goldwork from the medieval Western Sudan, but its intellectual and aesthetic legacy persists today.