South Africa—A Long Walk to Freedom

“When I walked out of prison, that was my mission, to liberate the oppressed and the oppressor both . . . We are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed. We have not taken the final step of our journey, but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road. For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.”

—Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, 1995

Willie Bester

b. 1956, Montagu, Western Cape Province, South Africa

Works in Kuils River, Western Cape Province

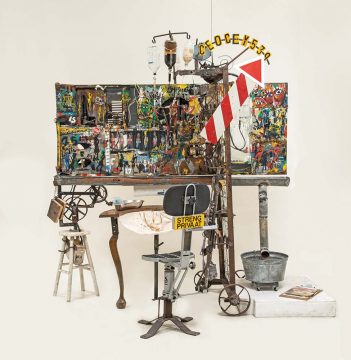

Apartheid Laboratory

1995

Mixed-media assemblage

Gift of Gilbert B. and Lila Silverman and Jerome L. and Ellen Stern, 2017-15-1

At first glance, the piece almost looks like a stage set. Look closely and elements of a clinical workspace emerge. This is a space in which we may imagine ourselves—as technician, or subject. “I am sometimes tempted to go to the seaside and to paint beautiful things from nature,” Willie Bester has said. “But I do not do it because my art has to be taken as a nasty medicine for awakening consciousness.” Filled with sharp edges and menacing contraptions, Apartheid Laboratory appears to be a vision of a particularly “nasty medicine,” indeed. Bester’s focus is on apartheid-era South Africa and its systems of racial classifications and their unfounded claims to scientific legitimacy and racial superiority. The work centers on seven small dolls, labeled with the seven racial categories recognized by South Africa’s government at the time—“White,” “Cape Coloured,” “Malay,” “Griqua,” “Chinese,” “Indian,” and “Other Asian.” Black South Africans were legally excluded and instead designated residents of “Bantustans,” territorial reservations that were politically designed to remove black claims to full citizenship. Apartheid in South Africa ended in 1994. Yet, as a stage set upon which anyone may seemingly enter, Bester cautions us through this work to remain awake to how menacingly present such pretensions to difference can continue to be. Oppressive systems, he notes, can be built from the most mundane, and ugly, of materials.

Villain in History: Hendrik F. Verwoerd

- Verwoerd built a reputation in South Africa as the founder of a newspaper through which he promoted pro-Fascist, anti-Semitic, and racist ideas.

- Shortly after the 1948 election that brought the Afrikaner-dominated National Party to office, Verwoerd became minister of native affairs—through which he implemented much of the legal architecture of apartheid.

- After becoming Prime Minister in 1958, Verwoerd moved to consolidate the apartheid state. He oversaw the invention of “Bantustans,” reservations justified as (fictional) ‘homelands’ for the country’s African majority to which they were to be exiled and legally bound. Through these he was able to fully disenfranchise non-white South Africans.

- Growing in power throughout his premiership, Verwoerd narrowly won a referendum to turn South Africa into a republic in 1961. Ever more isolated on the international stage, Verwoerd’s government built a military and police state and banned all black political organizations.

- Verwoerd was assassinated on Sept. 6, 1966—he was stabbed on the floor of the South African Parliament.

“…your Government, after receiving a mandate from a section of the European population, decided to proclaim a Republic on 31 May…Your Government, which represents only a minority of the population in this country, is not entitled to take such a decision without first seeking the views and obtaining the express consent of the African people…Under this proposed Republic [it is feared] your Government, which is already notorious the world over for its obnoxious policies, would continue to make even more savage attacks on the rights and living conditions of the African people.”

— Letter from Nelson Mandela to Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd, April 20, 1961Willie Bester

b. 1956, Montagu, Western Cape Province, South Africa

Works in Kuils River, Western Cape Province, South Africa

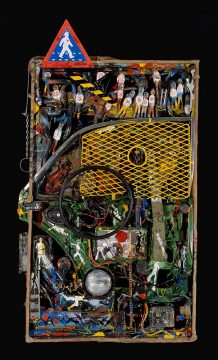

The Notorious Green Car

1995

Metal, paint, burlap, glass, plexiglass, bone, plastic, cloth, wood, rubber, paper, wire

Museum purchase, 96-26-1

Imprisoned himself under apartheid for loitering, the artist Willie Bester memorializes the history of harassment and oppression in South Africa’s black settlements. The Notorious Green Car’s mesh window screen recalls police vehicles used to patrol and terrorize black settlements. Bester created this large-scale, bright conceptual work to keep the memory of such oppression alive.

Hero in History: Steve Biko

- Frustrated by the lack of black voices in the anti-apartheid groups he observed while a student at university, Biko founded the South African Students Organization (SASO) in 1968, which sought to resist apartheid through political action.

- Biko and SASO promoted the Black Consciousness Movement, which promoted black self-empowerment and pride in the face of both the localized racism of the apartheid state and global post-colonial realities. Biko was placed under a government banning order in 1973.

- Following the 1976 Soweto uprising—protests by over 20,000 students against laws restricting education to the use of the Afrikaans language, brutally suppressed by the police—Biko was arrested.

- While in police custody, police officers tortured and beat Biko severely, causing his death. Those responsible were never tried.

- In death, Steve Biko became a global symbol—of the apartheid state’s amoral violence, but also of resilience, dignity, and pride.

“The most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

—Steve BikoWillem Boshoff

b. 1951, Johannesburg, South Africa

Works in Johannesburg

Prison Sentences

2010

Belfast black granite

Museum purchase, 2016-5-1

Prison Sentences reflects upon the marking and passing of time—here, the jail time served by some of South Africa’s most notable apartheid-era political prisoners. Each tablet is inscribed with the days, weeks, months, and years served by Nelson Mandela and seven other political prisoners who were initially sentenced to life imprisonment at the close of the Rivonia Trial held in June 1964.

Of the work, Willem Boshoff has said:

“The word 'sentence' refers to the term a prisoner serves, but it also denotes a grammatical whole with . . . an ending. Naming the work Prison Sentences alluded to the second meaning, the idea that one would expect a sentence to end. I wanted to evoke . . . a meditative quality arising from . . . counting days and passing time, to the point at which you lose yourself completely . . . Black granite is the material of a graveyard [and of] memorials. Each panel is reflective, so you see yourself in it.”

Heroes in History: “The Rivonia Eight”

- Leaders of the African National Congress (ANC) and other anti-apartheid resistance groups were arrested at a farm in Rivonia, a suburb of Johannesburg, on July 11, 1963. The ANC had been operating underground since the Sharpeville Massacre (April 1960) of 67 protestors by the police.

- Two defendants managed to escape from prison; the remaining eight faced charges accusing them of planning acts of guerilla warfare, of accepting aid from foreign supporters, and of promoting communism, among others.

- The United Nations Security Council condemned the trial and began the process of constructing a regime of international sanctions that restricted the South African government on the global stage.

- Mandela’s final speech from the dock, in which he bravely faced the possibility of a death sentence, would mark the last time the South African people heard from the resistance leader until his release from prison on Feb. 11, 1990.

“During my lifetime I have dedicated my life to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live for and to see realized. But, my Lord, if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

—Nelson Mandela, speaking from the dock at the close of the Rivonia TrialThe names and sentences completed by the Rivonia prisoners are inscribed on each tablet:

Nelson Mandela: 11 Jun 1964 - 11 Feb 1990 (9,377 days)Ahmed Kathrada: 11 Jun 1964 - 15 Oct 1989 (9,269 days)

Walter Sisulu: 11 Jun 1964 - 15 Oct 1989 (9,269 days)

Raymond Mhlaba: 11 Jun 1964 - 15 Oct 1989 (9,269 days)

Elias Motsoaledi: 11 Jun 1964 - 15 Oct 1989 (9,269 days)

Andrew Mlangeni: 11 Jun 1964 - 15 Oct 1989 (9,269 days)

Govan Mbeki: 11 Jun 1964 - 5 Nov 1987 (8,548 days)

Dennis Goldberg: 11 Jun 1964 - June 1985 (± 8,030 days)

Nelson Mandela

1918–2013, b. Mvezo, South Africa

The Limestone Quarry

2002

Watercolor on paper

Gift of Cary Frieze, in memory of his parents Rose and George Frieze, and in honor of the family of Nelson Mandela,

While the stones of Robben Island brutalized his body, Mandela also used them as a site to expand the mind. Mandela was forced to work daily in a limestone quarry, where the searing glare from the white stones eventually damaged his eyesight. On the island, Mandela was almost wholly cut off physically from the outside world. Yet, using texts smuggled in from the mainland, he established “The University,” through which the prisoners taught a range of subjects—including art—to each other. Despite his decades of internal exile, the memory of Mandela—the lawyer, the activist organizer of civil disobedience campaigns, the militant leader of the armed struggle, the imprisoned martyr—lived on in South Africans’ imaginations. Upon his release, the political platform that those decades of memories provided helped to lift Mandela into the negotiations to establish democracy in South Africa—and, eventually, into the presidency itself. This work, created by Mandela upon a return visit to Robben Island after leaving power in 1999, is a part of a series he created reflecting upon scenes of his homeland and memories of the struggle that transformed it.

WikiMedia Commons

Hero in History: Nelson Mandela

- Born to Xhosa-speaking parents in the Thembu royal family, Mandela took it upon himself to study law at university. He and Oliver Tambo established a law firm in Johannesburg in 1952, offering free or low-cost counsel to black South Africans.

- Mandela helped organize the African National Congress (ANC) Youth League, which advocated for nationwide civil disobedience campaigns aimed to highlight the iniquities of apartheid. His growing profile led to arrests and harassment from the state.

- After the Sharpeville Massacre (1960), Mandela was convinced that only armed struggle could end apartheid. He cofounded the ANC’s militant wing.

- Arrested and tried for treason and sabotage, Mandela was sentenced to life in prison in 1963. While subjected to brutal treatment inside prison walls, Mandela became a global symbol of both oppression and hope for those outside.

- Upon his release from prison in 1990, Mandela negotiated with President F.W. de Klerk to organize free and fair elections. He had to strike a balance between keeping dialogue open while maintaining political pressure through the ANC. Mandela and de Klerk shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993.

- As South Africa’s first black president (1994–99), Mandela worked to assure passage of a new constitution—based on majority rule, but guaranteeing minority rights and freedom of expression.

When I walked out of prison, that was my mission, to liberate the oppressed and the oppressor both . . . We are not yet free; we have merely achieved the freedom to be free, the right not to be oppressed. We have not taken the final step of our journey, but the first step on a longer and even more difficult road. For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.

—Nelson Mandela, Long Walk to Freedom, 1995Kay Hassan

b. 1956, Johannesburg, South Africa

Works in Johannesburg

First Time Voters

1994–95

Paper, glue, staples

Museum purchase, 96-32-1

Kay Hassan used scraps from a billboard located near his studio to create this image of citizens of all colors and creeds anxiously waiting in in April 1994 line to cast their first vote, after the last of the apartheid laws were repealed, to create a democratic national government charged with writing a new constitution. The African National Congress (ANC) won 62 percent of the vote and formed a government of national unity with the Inkhata Freedom Party and the former ruling National Party.

Hassan’s use of everyday recycled materials recalls earlier South African's graffiti and poster arts, which afforded artists an inexpensive means for artistic creativity and for protesting the government's oppressive policies during apartheid.

Heroes in History: Citizen Voters

- On April 26-29 1994, nearly 20 million everyday South African heroes came together for the first time to shape their country’s future.

- These were the first South African general elections in which people of all backgrounds were allowed to take part. They were tasked with electing a new National Assembly, which would then write a new constitution for the country.

- The African National Congress (ANC) won 62% of the vote, and formed a government of national unity with the Inkhata Freedom Party and the formerly ruling National Party.

- The new National Assembly elected Nelson Mandela president. April 27 is a public holiday in South Africa—Freedom Day.

“All of my life had been spent in the shadow of apartheid. And when South Africa went through its extraordinary change in 1994, it was like having spent a lifetime in a boxing ring with an opponent and suddenly finding yourself in that boxing ring with nobody else and realizing you’ve got to take the gloves off and get out, and reinvent yourself.”

—Athol Fugard, South African playwrightSue Williamson

b. 1941, Lichfield, England

Works in Cape Town, South Africa

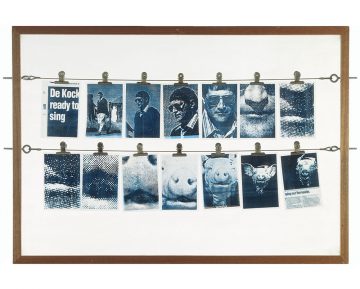

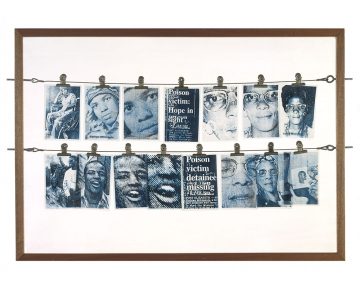

Cold Turkey: Stories of Truth and Reconciliation (“De Kock Ready to Sing” and “Poison Victim)

1996

Acetate, steel, plexiglass, wood

Museum purchase, 97-21-1.1-2

Hero in History: Archbishop Desmond Tutu

- Ordained an Anglican priest in 1961, Tutu rose through the church hierarchy to become general secretary of the South African Council of Churches—a position in which he gained global prominence as an advocate for non-violent resistance to apartheid.

- Desmond Tutu received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984.

- Tutu was elected archbishop of Cape Town in 1986, making him the highest Anglican authority in the country. Not known for holding back his opinions, Tutu earned a reputation for his incisive, wry, and often humorous insights. He also promoted the vision of a democratic South Africa as the “Rainbow Nation.”

- President Nelson Mandela asked Tutu to chair the Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 1996-1998. Promoting a vision of restorative justice and determined to hear from the “little people” whose suffering had been ignored, Tutu was sometimes openly overwhelmed with the emotion of the painful testimony. The Commission took over 22,000 statements.

- Approaching retirement, archbishop Tutu was awarded the U.S. Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009.

“There are different kinds of justice. Retributive justice is largely Western. The African understanding is far more restorative—not so much to punish as to redress or restore a balance that been knocked askew.”

—Desmond Tutu, 1996“Without forgiveness there can be no future for a relationship between individuals or within and between nations.”

—Desmond Tutu, 2000Sue Williamson

b. 1941, Lichfield, England

Works in Cape Town, South Africa

Winnie Mandela and the Assassination of Dr. Asvat

1999

Lithograph on paper with plastic film

Museum purchase, 2002-17-1

Hero in History: Winnie Madikizela-Mandela

- Trained as a social worker, Winnie Madikizela met Nelson Mandela in 1956, and became his second wife two years later.

- During the 27 years of Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment, Winnie Mandela was continually harassed by the government, facing banning orders, travel restrictions, internal exile, and 17 months in jail herself.

- Throughout her husband’s long imprisonment, she remained a resilient symbol of resistance, keeping his memory and message alive, in South Africa and beyond.

- The kidnapping and beating of four young activists, and the murder of one, Stompie Seipei, in 1988 forever damaged her reputation. She was convicted of kidnapping in 1991, though the sentence was later reduced. Nelson Mandela separated from her in 1992; they would divorce in 1996.

- Later in life, Winnie Madikizela-Mandela swung between moments of achievement and disrepute: She was a deputy minister in the first democratic government, but resigned under corruption charges. She was elected as a Member of Parliament, but was convicted of theft and fraud. She was reportedly at Mandela’s side as he lay dying in 2013, with his third wife, Graça Machel, but later sued his estate for control of his home (and lost).

“To those who oppose us, we say, ‘Strike the woman, and you strike the rock’.”

—Winnie Mandela, 1966"Together, hand in hand, with our matches and our necklaces, we shall liberate this country."

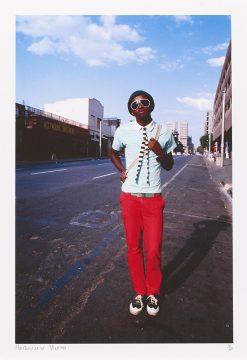

—Winnie Mandela, 1986, alluding to the notorious practice of lighting a gasoline-soaked tire, placed around the head of an opponent, ablaze.Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko

b. 1977, Bodibe, North West Province, South Africa

Works in Nîmes, France

Kepi Bree Street

2006

Digital print with pigment dyes on cotton paper

Purchased with funds provided by the Annie Laurie Aitken Endowment, 2011-7-1.4

Hero in History: Brenda Fassie

- A precocious and talented singer from a young age, Fassie made it big with a hit single, “Weekend Special,” at the age of 19, propelling her next album to multi-platinum status. In the 1990s, she became associated with kwaito, a genre of house music that sampled African sounds.

- She was celebrated as a voice of South Africa’s disenfranchised—during apartheid, and after.

- Fassie was often compared to the American pop singer Madonna—for the fearlessness with which she promoted her image, but also for the controversy that followed with her. Fassie struggled with drug addiction, and endured turbulent relationships with men and women in the public spotlight.

- Fassie publicly came out as a lesbian in 2003.

- In addition to her music, Fassie is remembered as a pioneering fashion icon, who died tragically young. Brenda Fassie delighted in breaking style taboos and innovating new trends.

“I’m a shocker. I like to create controversy. It’s my trademark.”

—Brenda Fassie, 1998“I’m going to become the Pope next year. Nothing is impossible.”

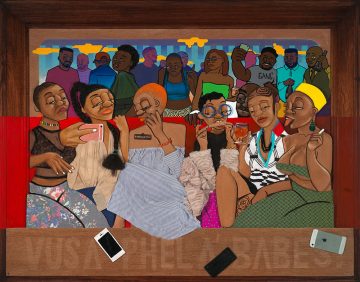

—Brenda Fassie, 1999Dada Khanyisa

b. 1991, Umzimkhulu, KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa

Works in Cape Town, South Africa

AMA #WCW

2017

Acrylic and mixed media on wood

Gift of Shari and John Behnke, 2018-11-1

Heroes in History: Beverly Palesa Ditsie and Simon Tseko Nkoli

- Ditsie and Nkoli are activists who had an important early role in creating legal and cultural space for LGBT people in South Africa in the early 1990s. Together, they were part of a cohort of activists who founded GLOW (Gay and Lesbian Organization of the Witwatersrand), the first national black LGBT organization in South Africa.

- A committed activist, Beverley Palesa Ditsie was the first out lesbian woman to address the United Nations on LGBT rights, speaking the Beijing Women’s Conference in 1995.

- Arrested as an anti-apartheid activist, Simon Nkoli came out while in prison. He used the moment to try to change the attitude of the African National Congress (ANC) toward gay rights.

- After 1994, Nkoli met with President Mandela and campaigned for the inclusion of protections for LGBT people in the new constitution. In 1996, South Africa became the first country to constitutionally prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation.

- Together, Ditsie and Nkoli organized the first Pride March in Africa, in Johannesburg in 1990.