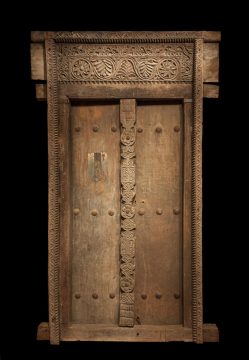

Siyu, Pate Island, Lamu County, Kenya

Doorframe (detail)

c. 18th to 19th century

African mahogany

Lamu Fort Museum, National Museums of Kenya

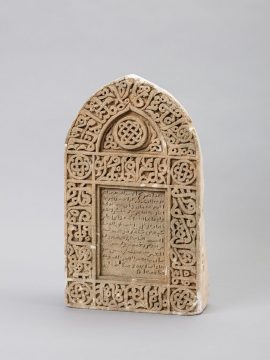

On the coastal headlands of eastern Africa, monumental stone marks the border zone between the African continent and the Indian Ocean. Since at least the 13th century, locals have built stately stone houses, tombs, and mosques, which have made Swahili towns and cities visible from great distances. The forms of this elite architecture changed over the centuries and varied from town to town, but they were always built of local coral limestone. This materiality—the weighty mass of coral stone—mediated human experience on the Swahili Coast in fundamental ways for centuries.

The decorative features of stone architecture are a complex fusion of cultural strands, including those from mainland Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, and South Asia. Overseas influences are evident in all the intricate woodwork and stone sculptures featured in this section. Carved doorways are an ancient Swahili form, but their surfaces, for example, have sculptural forms found in India. By the 19th century, wood-carvers fused Gujarati, neo-Gothic, and British Raj imagery and styles in a playful combination of many places and periods. The most wealthy patrons imported entire doors and windows from places like Mumbai, which signaled their ability to consume the artifacts of global modernity.

The Architecture of Elsewhere

The carved doorframes and windows found on the Swahili Coast represent a rich tradition stretching back to the late 17th century. The earliest extant dated example was made in 1694, but the practice of door carving grew dramatically during the 18th and 19th centuries in coastal cities such as Zanzibar Town, Lamu, and Siyu.

A great variety of decorative motifs, including rosettes, lotus leaves, and other floriated designs, animate the surfaces of these heavy wooden structures; rope, palm, and chain-link designs are common as border treatments. These, plus geometric and other abstract designs and flourishes of arabesque and calligraphic styles, constitute a veritable archive of aesthetic languages originating from places throughout the western Indian Ocean rim—all inventively combined by Swahili artists in the service of their patrons.

The styles are typically divided into two broad categories, identified as either Bajun or Zanzibar. The former, associated with northern Kenya, is distinguished by low-relief, geometric motifs. The latter, associated with the island of Zanzibar, is noted for higher relief and organic designs, possibly of Omani influence. Both types of design were used throughout the Swahili Coast.

Swahili artist

Bagomoyo, Pwani Region, Tanzania

Door

19th century

Wood, metal

National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Rod and Nancy E. MacDonald, 2013-3-1

Swahili artist

Kilindini, Mombasa County, Kenya

Tombstone

1462

Coral rag (limestone)

Mombasa Fort Jesus Museum, National Museums of Kenya, 98.2.220