Wasini Island, Kwale County, Kenya

Drum (ngoma kuu)

c. 17th century

Wood with possible cowhide

Mombasa Fort Jesus Museum, National Museums of Kenya, 98.2.211

A rich confluence of cultures has long informed and animated Swahili arts. The objects in this section testify to the types of intercultural exchange, competition, and mobility that have shaped the history of the Swahili Coast.

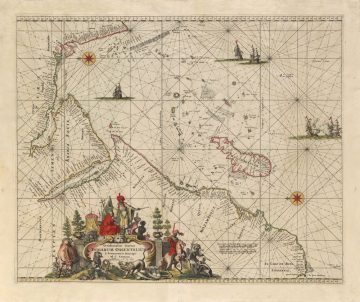

Swahili networks of trade historically reached far into the African mainland. Terrestrial routes between the Swahili Coast and regions along the caravan paths to Lake Tanganyika were essential to the economies of eastern and central Africa starting in the 14th century. These channels also acted as conduits for the exchange of aesthetic sensibilities and artistic practices.

The global demand for Africa’s resources—ivory, timber, grain, and even people—had devastating and brutal consequences. By the mid-19th century, many Africans from other parts of central and eastern Africa were violently dislocated and taken to the East African coast as enslaved laborers to work on coastal and island plantations of the Indian Ocean. Societies such as the Manyema, Makonde, and Zaramo were deeply fractured, but they reconstituted; their resilience is amply evident in several artworks on view.

Seafaring arts point to the role of Swahili merchants and sailors in shaping the navigational histories of the Indian Ocean. Lavish gifts of gold and silk bestowed upon American merchant-consuls by the sultans of Zanzibar in the 19th century demonstrate the growth of Africa’s political and commercial ties across the Indian and Atlantic Oceans.

The objects in this introductory section share a multistranded history that links many actors—African, Arab, European, and South Asian—across time, land, and sea. Together they shed light on the diverse facets of the arts of the Swahili Coast.

Slavery on the Swahili Coast

The enslavement of African peoples and their incorporation into economies of production and exchange throughout the Indian Ocean region have an even longer history than that of the transatlantic trade. Atlantic trafficking began in the 15th century when captive peoples from western and central Africa fed Europe’s need for mine and agricultural workers for plantations in the Americas.

The East African trade in captive humans, on the other hand, was connected to demand from the Arabian Peninsula and India from as early as the seventh century. Captives were taken from eastern and central Africa to Yemen, the Persian Gulf, India, and the Swahili Coast to work as domestic servants, sailors, divers, and mine workers.

Portuguese colonization in the 16th century, and subsequent alliances with the merchant princes and ruling dynasties of Oman, increasingly connected the aristocratic families of Swahili cities to wider capital markets, but also exposed them to greater imperial pressures. Meanwhile, the outlawing of the Atlantic trade in the 19th century led traders to look elsewhere for enslaved Africans who could work on plantations in the Americas and on Indian Ocean islands.

Driven by increasing global demands for East African commodities, Sultan Seyyid Said bin Sultan of Oman moved the capital of his commercial empire from Muscat, in the Arabian Peninsula, to Zanzibar in the mid-1830s. By 1837 Zanzibar had become the seat of the British-backed Omani Sultanate and soon thereafter a British protectorate. Clove plantations using forced labor were established in Omani-held regions of the Swahili Coast, such as Zanzibar and Pemba.

While institutions of bondage and slavery had existed in the past, the dehumanizing cruelty and scale of 19th-century plantation slavery forever changed the region. Slavery was finally abolished in Zanzibar in 1897 and in Kenya in 1907. The expansion of commodity markets during this period was built in part on terror and disruption. The violent separation of families and refugee migrations led to the creation of new identities in communities stretching from the coast deep into regions of the eastern Congo basin.

Makonde artist

Lindi or Mtwara Region, Tanzania or Cabo Delgado Province, Mozambique

Mask (lipiko)

Mid-20th century

Wood, pigments

QCC Art Gallery of the City University of New York, 13-02-03

Frederick de Wit

1629–1706, b. Gouda, The Netherlands

Worked in Amsterdam

Portolan chart Indiarum Orientalum (source: Harmonia macrocosmica, pl. 56)

Map, published in The Netherlands

1708

The Board of Trustees for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on behalf of its Rare Book & Manuscript Library

Zaramo artist

Pwani or Dar es Salaam Region, Tanzania

Box zither

20th century

Wood

National Museum of African Art, gift of Allen and Barbara Davis in honor of Bryna Freyer, Curator, National Museum of African Art, 2015-4-17

Swahili artist

Zanzibar, Tanzania

Chair (kiti cha enzi)

19th century

Wood, plant, fiber, ivory

Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts, gift of Miss Ruth R. Ropes, Mrs. Mary R. Trumbull, and Mrs. Elizabeth Williams, 1940, E33723