Within a decade of its invention in the 1830s, photography—one of the 19th century’s most revolutionary media—became essential to Swahili practices of self-fashioning. European ethnographers used daguerreotypes (an early photo-making technique) to document individuals they encountered on the coast. Later, commercial photography studios, primarily run by merchants from South Asia, who opened the first ones in Mombasa and Zanzibar by at least the 1860s, became wildly popular on the Swahili Coast. From the 1870s until the 1970s, people from the East African coast, the Arabian Peninsula, South Asia, and Europe all frequented these studios to have portraits made or to buy images of others.

Photography’s long history in Africa attests to the continent’s global interconnectivity, but it also expressed local cultural interests. Especially before World War I, photographs functioned as objects of good taste; women on the Swahili Coast loved displaying them in their living rooms or reception spaces as emblems of their cosmopolitan sense of design. For local consumers, photographs were tantalizingly exotic, endowed with a foreign aura that made them perfect artifacts for display and pleasure. Photographs often communicated in ways that had to do with their function as objects, dense with texture and surface minutiae.

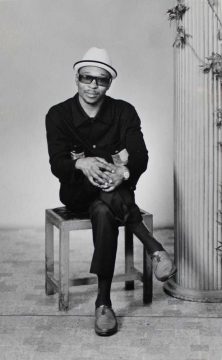

By the 1950s and 1960s, sitting for one’s photographic portrait was a popular leisure activity particularly for young people, who were drawn to big cities such as Mombasa, Dar es Salaam, and Nairobi. People from all walks of life delighted in new fashions to demonstrate their modern sensibilities in front of the camera.

Parekh Studio

Man Sitting

Mombasa, Mombasa County, Kenya

1966

Collection of Heike Behrend

Narandas Vinod Parekh (b. 1923), a Kenyan whose family emigrated from India to Mombasa in the 1800s, trained with local photographers in the 1930s. In 1942 he founded a studio in Mombasa and was celebrated for his ability to fulfill his clients’ desires. Depending on their wishes, he worked to create elegant, respectable, hip, or sometimes sensual portraits. To keep his work fresh and innovative he traveled internationally and regularly visited Mombasa’s cinemas, which mainly played Hollywood and Bollywood movies.

People often visited Parekh’s studio to mark important events, such as weddings, reunions, graduations, and birthdays. By the 1960s, teenagers and young adults were visiting the studios by themselves, or with their friends or lovers, to create playful—even daring—pictures that were not meant to be seen by their relatives.

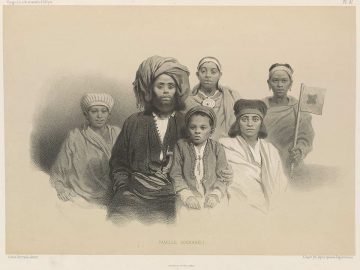

Adolphe Jean Baptiste Bayot

1810–1871, B. Alessandria, Piedmont, Italy

Worked in Paris

Famille Souahheli (Swahili Family)

Lithograph, after daguerreotype created in 1848 in Mombasa, Kenya

Smithsonian Libraries

Guillain’s portraits of individuals he encountered on the coast—from rulers to enslaved people—are among the earliest known examples of photography from the region. The first widely available photographic process, daguerreotypes involved the exposure of a chemically treated silver plate to an image created by a simple camera and sunlight.